Oh, deer. Whitetails and Minnesota's future forests

Now that Rudolph is back at the North Pole and out of earshot, we need to talk about his cousin. No, not Dasher or Dancer. I’m talking about Bambi: those white-tailed deer that nibble on your garden plants and rub the bark off the saplings you planted in the backyard. While these habits may be annoying (enough for some folks to try things like spraying animal urine around their garden), they pale in comparison to the effects an overabundance of deer are having on Minnesota’s forests.

Around the turn of the 20th century, unregulated hunting had decreased the nationwide deer population to around 500,000 individuals. But thanks to the Lacy Act and the establishment of state and federal conservation agencies, deer — and other wildlife populations — have not only recovered but, in some cases, surpassed historical levels. Today, the U.S. deer population is well over 30 million, the majority of which are whitetails. In Minnesota, estimates put the deer population at over one million, with some counties experiencing densities of over 24 deer per square mile. While this may seem high it pales in comparison to Wisconsin, where some counties are home to up to 66 deer per square mile.

Tasty natives

While a boon to the hunters, overabundant deer are having other, less desirable effects, especially on our forest ecosystems. The problem? Deer eat. A lot. And like most humans, they tend to prefer certain foods.

Their diet primarily consists of things like wildflowers (forbs), leaves, buds, new twigs, nuts, and some grasses and sedges (plus, perhaps, some fresh vegetables from your garden). Throughout the year, more common species like red maple and dogwood are staples, as they're especially palatable and often nutrient-rich. Ecologically, we don’t see large declines in those species. It's the less abundant ones that deer negatively impact, and unfortinately whitetails find many browse-sensitive and important native plant species particularly tasty. In the springtime, hungry deer seek out trillium and trout lily, for example. And as summer progresses they go searching for legumes and jewelweed. Only when their preferred food sources are not available or have been exhausted will they move on to less tasty or nutritious foods.

Deer browse lines are often visible at the edges of forests and woodlots.

With so many deer munching on tasty native foliage, less common plant species are experiencing population declines and aren't as able to regenerate. For example, trillium populations have experienced widespread decline due to deer browse, which often exacerbates the impacts of drought and other factors. In fact, for a normal forest tree species, studies suggest that successful regeneration requires fewer than 21 deer per square mile, and for browse-sensitive species that number declines to between 3 and 10.

Unpalatable invasives

What deer don’t eat, however, are many of our most common invasive plants. For example, deer rarely eat buckthorn and garlic mustard, two non-native invasive plants that dominate many of Minnesota’s forest and woodland understories, especially in the central and southern parts of the state. As these species outcompete native plants, the remaining native individuals are more susceptible to deer browse as they experience a higher deer-to-plant ratio. As deer continue to eat those natives, they free up space and other resources that the invasive species are often poised to take advantage of. This shifts the competitive balance in favor of the invasive species, allowing them to increase their abundance.

Deer browse of native species may open up space for invaders such as garlic mustard. Photo credit: nature.org

Plus worms and warming weather

While this is bad enough, earthworms and climate change can also play a role in this system. Invasive earthworms negatively affect many native plant species. They can cause leaching of water and soil nutrients, increase the bulk density of soils, and change the overall germination environment by removing the leaf litter and duff in which many species have evolved to germinate. Along with deer and invasive plants, these earthworms contribute to the increased lack of regeneration of native trees and understory plants, and a more general “forest decline syndrome.”

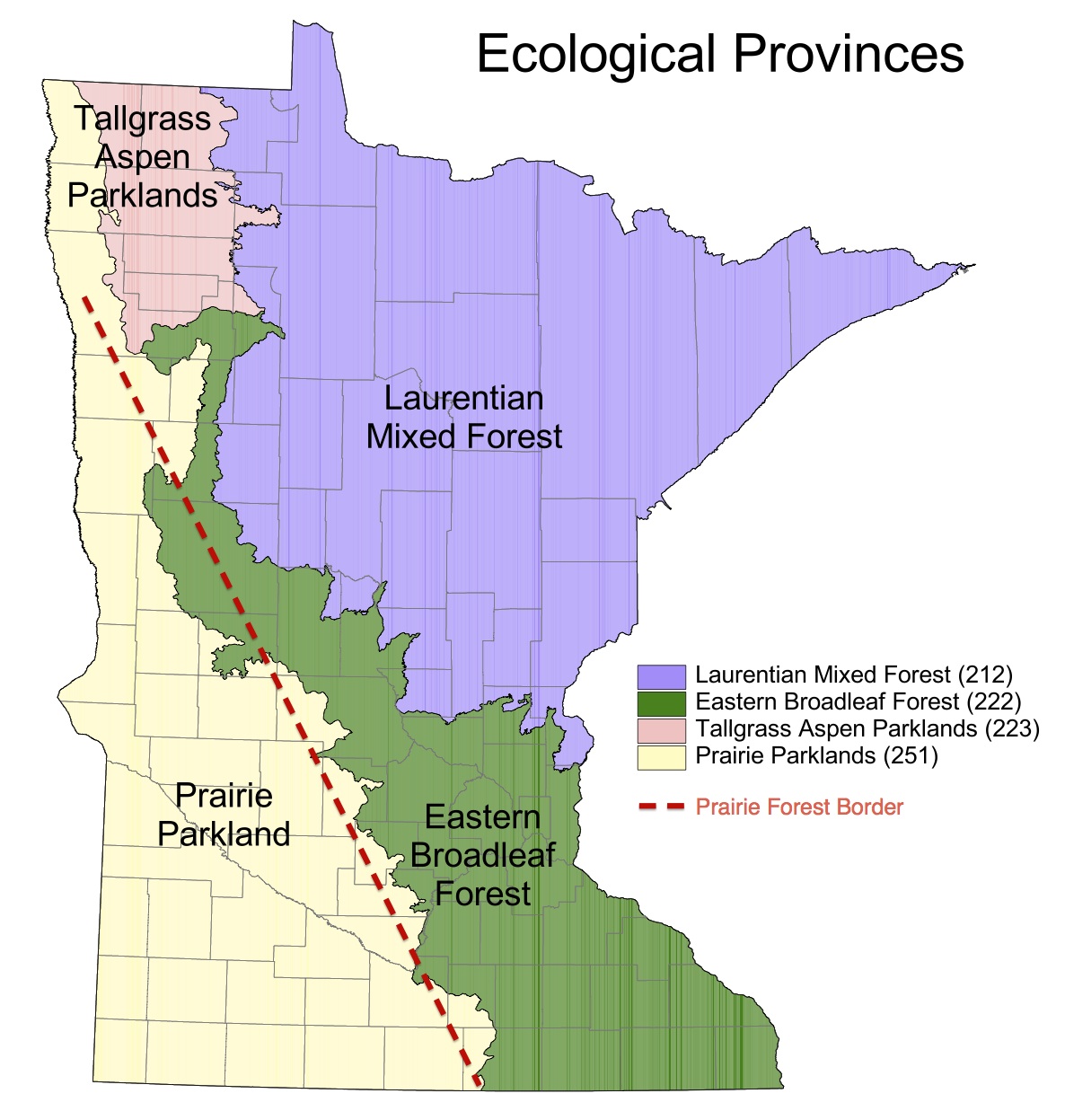

Climate change only compounds the situation. Historically, as the climate warmed, the current prairie-forest border that runs diagonally across the state shifted further east. With modern climate warming, it is expected to do so again. Climate change will bring an increase in fires, severe storms and other disturbances (defoliating insects, for example) that will remove existing forests, and we are expected to experience more frequent droughts, making conditions less hospitable for forest growth. However, with deer and earthworms preventing the regeneration of tree species, there will be little besides shrubs and grasses to replace the forest, and forests at this border may undergo a rapid “savannafication,” meaning that the border will shift further and faster than it has in the past. This may also occur at a rate that prevents tree species from retreating northward, and deer will likely browse those more northerly individuals, leaving vacant niches that are likely to be replaced by invasive species more tolerant of the changing conditions.

The prairie forest border will likely shift to the northeast, and deer may play a large role in "savannification" of the landscape. Image modified from the original at: http://www.dnr.state.mn.us/ecs/index.html

... Makes management even more important

While this may sound like doom and gloom, all is not lost. Deer play an important role, and management of deer populations is one of the many steps we can take to ensure the health of our forests. Managing invasive plants will also help protect our native species. Finally, as the prairie-forest border shifts, it presents opportunities for the restoration of prairie and savanna habitat that once existed on a much larger scale in the state. Active management of the aforementioned factors will help ensure that we can create healthy native habitats, and won’t end up with low diversity prairies and buckthorn savannas.

--------------

Sources:

Rooney, TP and Goss, K (2003) A demographic study of deer browsing impacts on Trillium grandiflorum. Plant Ecol.

US Forest Service and UMN Department of Forest Resources and Extension. “Impacts of Deer Browse on Forest Regeneration Across the Northeastern United States.” (Video)

Frelich, LE and Reich, PB (2009) Will environmental changes reinforce the impact of global warming on the prairie–forest border of central North America? Front Ecol Environ.