Buckthorn: How can a shrub be so harmful?

Each year, hundreds of volunteers help remove buckthorn from FMR-maintained natural areas throughout the metro Mississippi River corridor. (Photo by Scott Woolridge)

Common buckthorn is a tall, understory shrub brought to North America in the early 1800s as an ornamental shrub, primarily to serve as a hedgerow. But this woody plant escaped from yards and landscaped areas long ago, spreading rapidly in forests, oak savannas and other natural areas.

Buckthorn is extremely hardy and able to thrive in a variety of soil and light conditions. It also outcompetes native plant species with its fast growth rate and distinctive phenology — buckthorn leafs out earlier in the spring and holds its leaves later into fall, allowing it to continue to grow when most native species are dormant.

Buckthorn also has few predators. Look closely at a buckthorn leaf and you'll rarely see any spots or small holes. It has no specific insect predators in North America. Deer also avoid it, instead munching on native species and furthering buckthorn’s competitive edge.

Combine these characteristics with this shrub's plentiful seed production and it's not hard to see how it can very quickly spread through a forest or other natural area.

Buckthorn is known for its bright, glossy leaves, which stay green late into fall long after most native plants have gone grey.

Why buckthorn matters

Impact on wildlife

To us humans, a glen full of buckthorn just looks like a lush sea of bright green leaves. But to butterflies, bees and insect-eating birds, it's the equivalent of a barren desert.

While birds (and sometimes mice) do eat buckthorn berries, it's often because it's the only available seed source. But buckthorn berries are not a good food source. They're low in protein and high in carbohydrates and produce a severe laxative effect in some animals. For smaller birds, the laxative effect can even be strong enough to result in death. Adding insult to injury, birds excrete the seeds and distribute buckthorn over long distances.

Buckthorn berries aren't as nutritious for wildlife as native plants' berries.

Facilitating other invasives

Other negative effects stem from buckthorn’s leaves. High in nitrogen and calcium, they are very palatable to decomposers like earthworms. Once they fall to the ground, they decompose rapidly and result in boom-and-bust cycles for available nutrients and the microbes and other decomposers that depend on them.

Buckthorn also alters the soil. Soil under buckthorn has higher nitrogen levels, which can encourage the growth of disturbance-loving, weedy species such as invasive garlic mustard. Buckthorn likely also facilitates invasive earthworms by keeping soil cool and moist, and by providing high-nutrient leaf litter.

Bad for the river and water quality

Finally, because buckthorn shades out and outcompetes native groundcover plants, it can harm water quality. Native groundcover helps stabilize soil and retain and absorb rainwater. Without these native plants, rain will quickly wash over exposed, bare soil (like that under buckthorn bushes) and into nearby bodies of water.

This increases erosion of the river gorge, lakeshores and streambanks. In many cases, as the rainwater travels it picks up pollutants: bits of asphalt shingles from our roofs, fertilizer from our yards, oil from the street etc, and then dumps it all, unfiltered, into the Mississippi River.

FMR Volunteers cut and haul buckthorn to make way for more diverse habitat. (Photo by Michael Marren Photography for FMR)

Removing buckthorn at an event

Volunteers do not need to learn about removing this invasive before helping to remove buckthorn at a habitat restoration event. FMR staff will provide a complete overview and brief training as well as all tools.

Most event listings specify whether volunteers will be pulling seedlings, using loppers or weed wrenches, or hauling pre-cut buckthorn. Some events are a mix of these activities and event staff will make sure each person has a task they're comfortable with. Also, when tool use or terrain make the event unsuitable for young children, this will be noted in the description on the events calendar.

Removing buckthorn at home

The information below is intended to provide an overview for those who enjoy learning about local ecology or who are wondering if they or someone they know has buckthorn in their yard and, if so, what they can do about it.

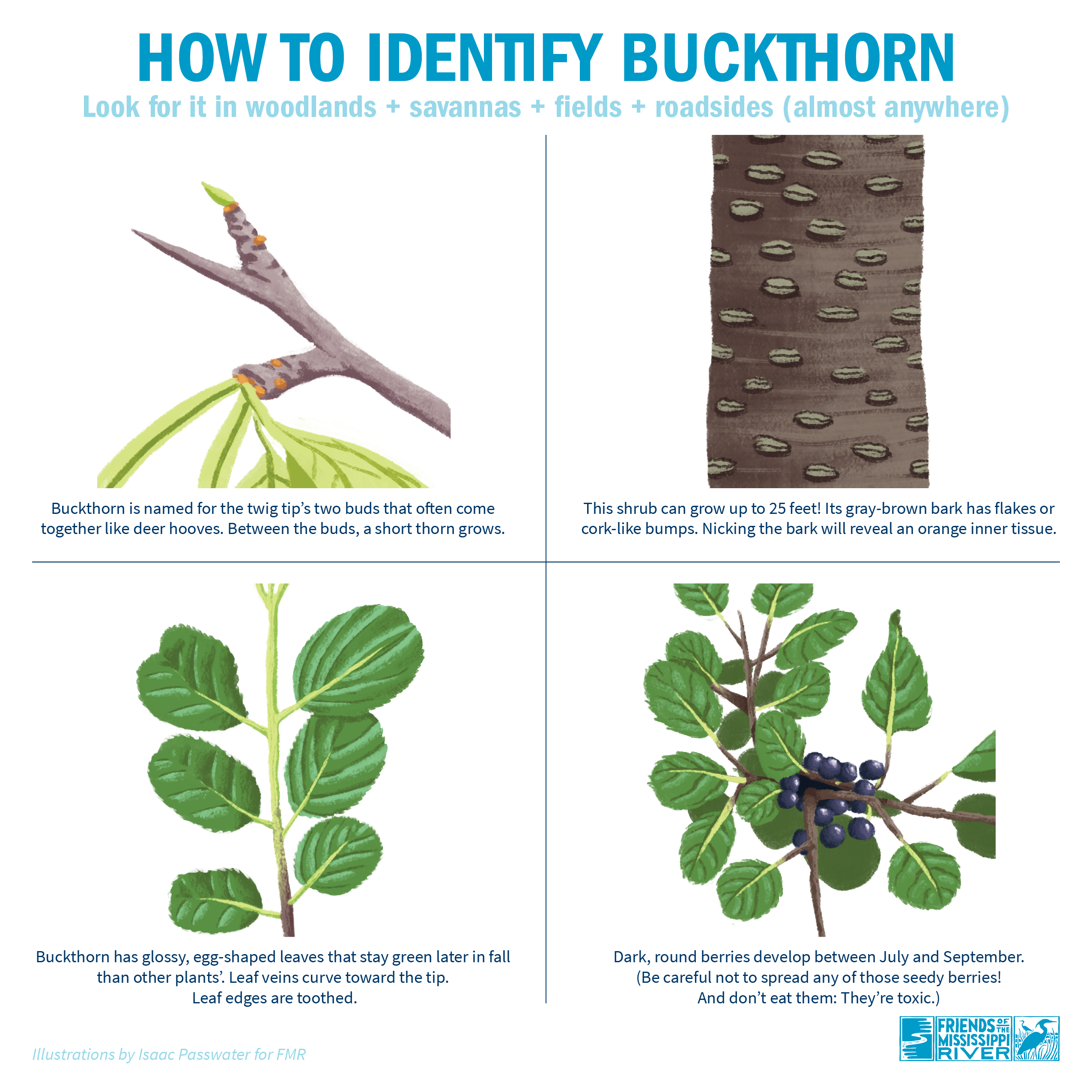

Identifying buckthorn

The first step to successful buckthorn removal: Know your plant! While not incredibly remarkable in any of its physical features, buckthorn is the only tree with all of the following characteristics:

- It is a tall, understory shrub, or small tree, reaching up to 30' in its maturity.

- The base of the shrub often contains multiple stems and its bark can appear cracked and flaky, with small white elliptical dots called lenticels.

- Nicking the bark will reveal an orange cambium or inner tissue distinctive to this species.

- The leaves are arranged alternately (though sometimes they appear almost opposite), bearing a broadly elliptical shape and tipped at the end. The sides are finely serrated, or small-toothed, and the texture is waxy. Because buckthorn leaves remain green even into late autumn, they are perhaps most easily recognizable at this time.

The City of Burnsville has an excellent buckthorn identification page, along with removal tips.

We made a buckthorn ID collector's card and flyer to make identification easier. (Thanks to Isaac Passwater Illustration for the images)

Removing smaller plants

For removing seedlings and smaller, younger buckthorn plants, simple hand removal works quite well. Pliers or a small shovel may also be used. With immature seedlings, roots are not yet deep, so it should be fairly easy to get the job done. Remember to shake the soil free from the roots so smaller plants can detach and decompose, and to fill any holes left by pulling out the plants.

If you have both large and small shrubs, a task that may seem too daunting even to begin, it's advisable to start with the larger, berry-producing individuals, then work down in size class as you go. Because only female buckthorn produce berries, this strategy can be used to slow the buckthorn's regeneration at any given site.

Removing larger shrubs

For larger shrubs, simple hand-pulling will not suffice. For medium-sized individuals - any plants with a "trunk" 0.5-2.5 inches in diameter - you'll need a Weed Wrench.

The Weed Wrench is easy to use. You clamp it tightly to the exposed stump and then pull back from the top, ripping the stump and shallow roots from the ground.

Last we checked, you could rent Weed Wrenches in the Twin Cities from Crown Rental, Reddy Rents, Hejny and Highway 55 Rental. There are probably many other rental places out there, and you may also try your local community group, Cooperative Weed Management Area, or city forester to see if they have a loaner program. FMR also owns a few that can be borrowed!

Weed Wrenches aren't ideal for areas with loose soil, slopes and diverse native plants. In these cases, a professional crew may be needed to use other control methods.

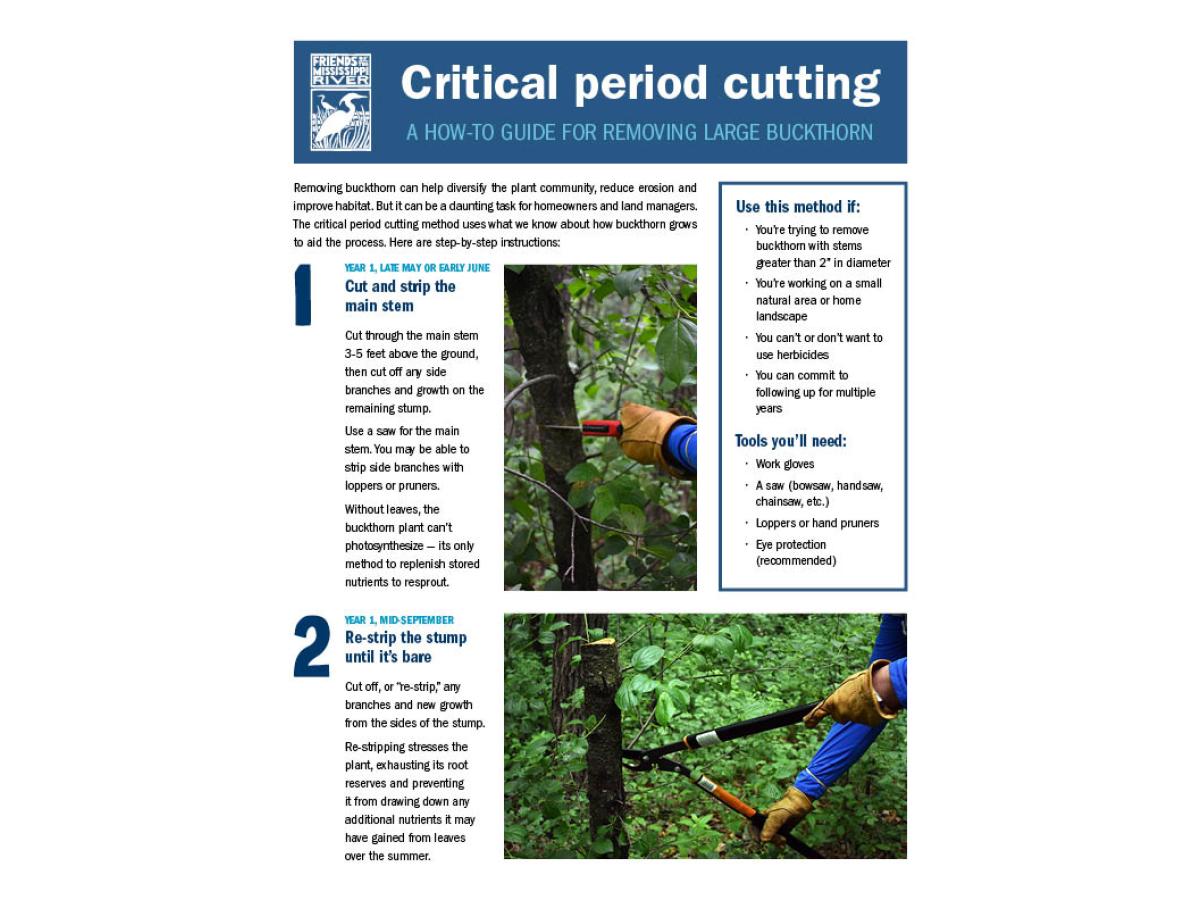

For even larger individuals, cutting down the shrub is the best option. Professional crews may use chain saws and brush saws and then treat the stump with herbicides to prevent regrowth, but homeowners and those averse to herbicide use can employ the critical period cutting method to removal a buckthorn plant in 1-2 growing seasons.

Getting away "clean"

Disposing of buckthorn brush can be tricky.

At events, volunteers help collect the branches for removal. Once taken away, the branches must be appropriately managed. This is particularly important when the branches contain seed-bearing berries. The best way to ensure that seeds will not germinate is to burn them. (Volunteers will not be asked to burn anything, of course.)

If you're removing buckthorn on your own property, contact the city for details about composting, burning permits, or inquire about woody brush pickup processes.

Followup

If you follow the steps listed above, the chances for successful buckthorn removal are high. However, because each buckthorn berry contains up to four seeds, seedlings may reappear despite your vigilance. It's best to revisit the site to check for seedlings. More important, many invaded sites need help to recover the native plant community. Seeding and planting can be especially helpful in the year after buckthorn removal in order to compete with new seedlings and to help restore viable habitat for wildlife. Even seeding with a simple native grass mix can do the trick.

It takes some effort, but persistence pays off. Many FMR restoration sites, including the beautiful oak savanna in the Mississippi Gorge Regional Park (a River Gorge Stewards site), were once buckthorn thickets and now provide excellent habitat and help improve water quality throughout the watershed!

---------

For further information on tackling buckthorn in your yard, visit the Minnesota DNR.

You may also want to check in with your community organization, neighborhood group or local watershed district about the possibility of assistance or matching grants to replace the invasives with watershed-friendly native species. Some cost-sharing programs are listed in FMR's Landscape for the River guide.