Snapping turtle hatchlings protected from predators

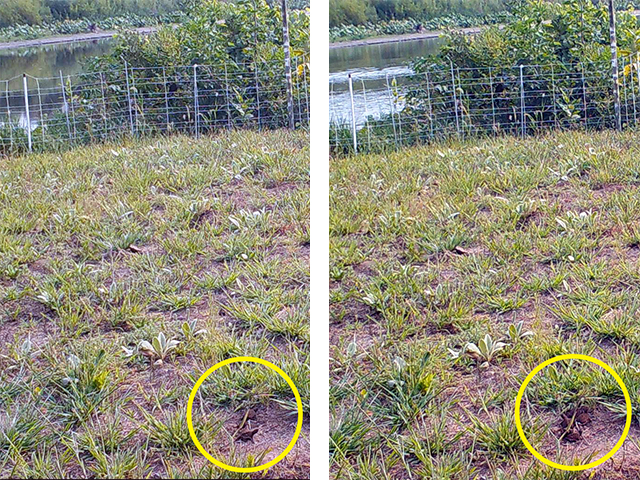

We finally have photographic evidence of baby snapping turtles hatching in peace thanks to our new wildlife nest enclosure. Photos taken by our wildlife cameras show hatchlings tunneling up from their nest and heading out in search of their first meals in the slow-moving backwaters around the Spring Lake Islands.

A haven for turtles (and for turtle predators)

Last May, just before turtle nesting season began, we finished installing this protective enclosure at Spring Lake Islands Wildlife Management Area near Rosemount.

Historically, turtle nests have abounded there. The site is located on a peninsula that juts into the Mississippi River. An open clearing makes this spot easily visible to passing turtles. And its sandy soils are ideal for a turtle to dig into for her nest.

However, the area is also highly trafficked by turtle predators. In 2017 the site was strewn with broken eggshells.

Turtles in, predators out

The enclosure structure we built allows turtles and sunlight in, but keeps out racoons, foxes, coyotes, possums and otters. To these mammals and other predators, turtle eggs are an easy, protein-filled snack.

The enclosure looks a little like a wire fence you might use to keep deer out of your vegetable garden. But there's a lot more to it. We are indebted to Carol Hall, Minnesota Biological Survey herpetologist, for helping us through the entire process from site selection to installation.

Boards frame the perimeter underground while landscape fabric and chicken wire extend out from the fence. These additions keep predators from tunneling or digging toward their prey. A solar panel charges all but the bottom wire of the fence, leaving a few inches for turtles to scoot through unharmed.

Can't small mammals squeeze their way under the lower wire? FMR ecologist Alex Roth thinks that the wires are a visual deterrent, and that predators are more likely to climb rather than slink through, recoiling after their first reach.

The long-awaited hatchlings

In the thousands of pictures taken by the wildlife camera in the turtle enclosure's first weeks in action, our ecologists discovered this photo of a mother snapper laying eggs in the sand.

At least five turtles nested inside the enclosure this season. Each probably laid between 10-100 eggs. Knowing the broods would hatch in late summer if they survived, FMR senior ecologist Karen Schik checked the wildlife camera's footage in late August. She hoped to see hatchlings from the mother caught on camera last May.

Though snapping turtles are Minnesota's largest turtles, babies could fit in a tablespoon. Still, Schik managed to spot them emerging. "We put a lot of effort into making these cages to protect turtle eggs from predation, so we really want to see that they are successful."

Unfortunately, she also spotted a mole tunneling within the enclosure. Though moles eat turtle eggs, Schik isn't too discouraged. "With less and less habitat available to turtles for nesting, many turtle populations are declining so any help we can give them is a positive thing."

For generations to come?

While this is the first season we've worked to protect turtle nests, it won't be our last. Thanks to funding from SeaLife Minnesota and support from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, we'll maintain this enclosure at Spring Lake Islands next season.

We're even adding another at William H. Houlton Conservation Area. We're lucky to be working with an Elk River Eagle Scout candidate on that project.

Up to 80% of turtle nests are lost to predation. When this project started less than two years ago, we hoped the protection provided by our enclosure would improve those odds.

Roth knows that turtles face survival challenges at all stages of life, but hatching is a milestone: "Seeing the photos of these hatchlings means we're already seeing the measurable impact of our work. We're helping these species escape one of the biggest hurdles to survival. That's a big deal."

Want to read more about the wildlife we encounter in the places we work to conserve and restore? Sign up for Mississippi Messages, our biweekly e-newsletter.