A stadium-sized drinking water supply dilemma

White Bear Lake water levels are falling as the underlying aquifer is depleted.

Photo: MPR News

As Mississippi Messages readers know, aquifer levels in the northeast metro area have declined dramatically in recent years, taking White Bear Lake waters levels down with them. With more than 70 percent of the regions water supply coming from groundwater, sustainable water supply planning is of critical importance to the economic security of the region.

Thats why the Minnesota Legislature funded a study by the Metropolitan Council to address long-term water supply planning for the Northeast metro area.

The draft report evaluates the feasibility of different approaches to restoring the aquifer that supplies drinking water to the area as well as supporting water levels in area lakes, including White Bear Lake.

These options have a common theme of increasing reliance on the Mississippi River as a drinking water source, thereby reducing pressure on the Prairie du Chien aquifer. Since only two percent of the metro Mississippi River is used for water supply, increased reliance on the river is both sustainable and preferable to our existing overreliance on groundwater.

The Metropolitan Councils preliminary draft report looks at several sustainable solutions for providing long-term water supply to the northeast metro area.

Approach 1: Connect some communities to the existing St. Paul drinking water system

The city of Saint Pauls regional drinking water system has the capacity to provide about 30 million gallons a day to neighboring communities. The Met Council looked at a few options within this approach:

- Option 1A: Extend water supply to North St. Paul only. This would cost about $5 million, with annual operating costs of about $1.3 million.

- Option 1B: Install a new water main from the St. Paul Water Treatment Plant to serve six northeast metro communities (Vadnais Heights, White Bear Lake, White Bear Township, Mahtomedi, Shoreview, and North Saint Paul). This option would cost an estimated $155 million, with an annual operating cost of about $10 million.

Approach 2: Expand the St. Paul drinking water system and connect 13 new cities

To reach more northeast metro area communities, the St. Paul drinking water system would need a significant upgrade. This expanded system could eventually serve 13 new communities in three phases. These communities would include Vadnais Heights, White Bear Lake, White Bear Township, Mahtomedi, Shoreview, North Saint Paul, Lino Lakes, Centerville, Hugo Forest Lake, Columbus, Circle Pines, and Lexington. This system would cost about $623 million to build, with annual operating costs of about $18 million.

Approach 3: Build a new northeast metro area drinking water plant

Rather than build onto the existing St. Paul system, this approach would divert Mississippi River water through the north metro area to a new treatment plant in Vadnais Heights. The Met Council looked at a few options within this approach:

- Option 3A: A new treatment plant with a smaller distribution system could serve Mahtomedi, Shoreview, Vadnais Heights, White Bear Lake, and White Bear Township. This smaller system would cost about $230 million, with undetermined annual operating costs.

- Option 3B: A larger system serving seven additional communities (Centerville, Hugo, Lino Lakes and Circle Pines, Columbus, Forest Lake, and Lexington) would cost about $610 million, with undetermined annual operating costs.

The more comprehensive options (2 and 3B) offer a stadium-sized dilemma for Minnesota. At costs that are comparable to a new Vikings Stadium, these options provide water for 13 communities who will otherwise struggle to provide water to fast-growing populations.

However, the state lacks adequate funding for such an investment and has yet to determine if local communities would pick up the tab. Others have asked about the potential for both water pricing and conservation measures to reduce the needs (and costs) of a sustainable water supply system.

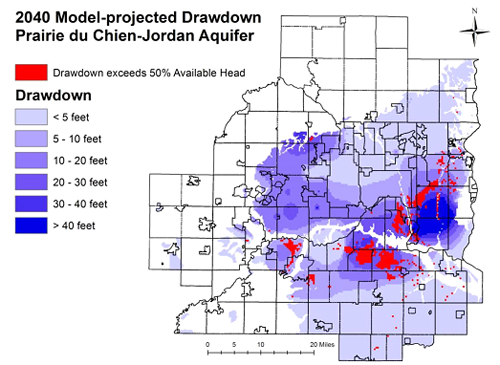

The projected drawdown of major regional aquifer levels if communities dont reduce their groundwater consumption.

Image: The Metropolitan Council

White Bear Lake augmentation

In addition, the report provides cost estimates for a shortsighted effort to pump water from the Mississippi River, treat it, and pipe it into White Bear Lake. This so-called augmentation approach would add another $50 million, and would be aimed at artificially raising White Bear Lake water levels.

The Met Council found that augmentation would not guarantee that White Bear Lake levels would be restored and maintained, and would not likely benefit other area lakes or groundwater aquifers.

Editorials from the conservation community (including FMRs own Whitney Clark) and local media outlets have panned that idea as an unwise and ineffective use of taxpayer dollars a conclusion supported by the Met Councils finding.

Summary

While the final draft of the Met Council report is not due until later this fall, the preliminary report indicates that providing sustainable water supplies to the northeast metro area will be no small task. However, given the costs to communities and private well owners if our aquifers continue to run dry, water supply planning is more important now than ever.

FMR will continue to monitor the Met Councils work and advocate for sustainable long-term solutions that ensure that the Twin Cities can meet its needs while protecting our surface water and groundwater supplies for future generations.

The full draft of the Metropolitan Council report (146 pages, 18 MB) is available for download.