Write to the River — Fall 2017 Prose & Poetry

The Mighty Mississippi gently flows between the bridge that connects the hillside and lowland. Photographer Tom Reiter captured the moment above with a paddleboat passenger enjoying the Big River and the iconic High Bridge in St. Paul. We asked readers what inspires them to reflect upon the river, and received a wide range of thoughtful responses. We hope their writing inspires you!

Write to the River is a creative writing project to inspire artistic engagement with our river environment. We invite you to share an original poem or short prose response to seasonal images along the Upper Mississippi River. Our next photo prompt and call for creative writing submissions will be in the December issue of our e-newsletter, "Mississippi Messages."

high bridge

by Ellen Fee

how many boats have split the water

under these arches,

under these stars?

centuries of sand piled on these shores,

legacy of glaciers and dust.

generations behind me

each time I trace the water

with my eyes,

watching the current

become sky.

Home

by Chelsi Kahl

My husband and I live on a houseboat. It is not large or glamorous. It is very small, very simple. People always ask, “Why did you decide to do that?” It is a strange question to answer; I think, “well, why not?” I do formulate an answer to explain what seems so natural to me. I explain that the river has always felt more home than any house. More than an apartment in the city or a house in the suburbs, the river is a peaceful place to rest my head. From childhood on, this river has been a source of calm, wonder, adventure, and growth. The essence of my answer is this- I did not choose the river; the river so easily chose me.

I work at a hospital in downtown Minneapolis; here, the noises, the people, and the tasks are constant. I observe that much of the city feels this way — rushed, distracted. How could I be a good nurse if I only knew chaos? For my patients and their families, I need to be calm, balanced, clear-headed; in such difficult times, a source of peace and focus is vital. The river is my reprieve.

The flow of this grand river reminds me that the world is constantly changing; life does not stand still. The seasonal rises and falls of the mighty Mississippi is sometimes a harsh but necessary reminder that nature is powerful, more powerful than you or me; we must take care of it and respect it.

When I see trash in the river, I wish I could bring the person who left it to this place so that they too could recognize the consequences of small and simple actions. I admire the stoic stance of the blue heron as I kayak by. He thinks I don’t see him, so I play along and admire quietly.

Every part of nature is felt here — the cold, the wind, the storms, the geese as they fly overhead in migration and the people too. People along the river feel nature so intimately. They feel the change of the season because they are a part of it. Just like the geese flying above or the beavers storing food for winter, we, the weird boat people, prepare too. Winter will not keep us away from the river. We will adapt and remain; no matter the circumstance, this river is home.

Notes from the Owner's Manual

by Jim Larson

To start, you need to invent gravity;

and give it time to work its way with things.

Then you find a slope and add some water,

lots of it, like from a dying glacier.

Congratulations! You’ve just made a river.

Or, on a good day, take two continents

and arrange a gradual collision.

Then you wait for several million years

to grow a mountain range. And after that

you let the continents relax. The ditch

you get will probably find an ocean.

Then just leave your handiwork alone.

The rain will find it and know what to do.

Let somebody else give it a name.

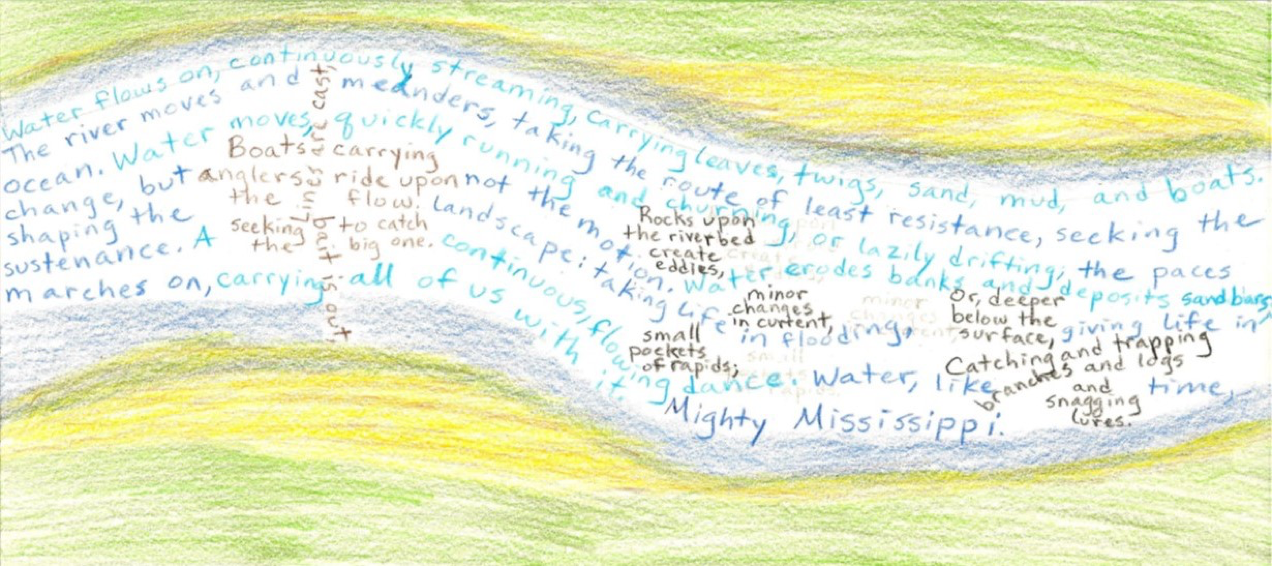

River concrete poem

by Christine Bronk

the Boat section (brown):

Boats carrying anglers ride upon the flow. Lines are cast, create eddies,

bait is out,

seeking to catch the big one.

the Rocks/Underwater log section (black):

Rocks upon the riverbed

create eddies,

minor changes in current,

small pockets of rapids;

Or, deeper below the surface,

catching and trapping branches and logs

and snagging lures.

the River section (various shades of blue):

Water flows on, continuously streaming,

carrying leaves, twigs, sand, mud, and boats.

The river moves and meanders,

taking the route of least resistance,

seeking the ocean.

Water moves, quickly running and churning,

or lazily drifting;

The paces change, but not the motion.

Water erodes banks and deposits sandbars,

shaping the landscape;

Taking life in flooding,

Giving life in sustenance.

A continuous, flowing dance.

Water, like time, marches one,

carrying all of us with it.

Mighty Mississippi

Empress

by Linda Moua

At any given moment

I feel as though I am guest on her flowing body

At this very moment

She provides passage to spy on carefully hidden neighbors

At any given moment

I could fall though her chilly surface and suffer an abrupt shock

At this very moment

She can only feel the towing of my paddles left to right

At any given moment

I look up to her thicket of verdant friends to find inner peace

At this very moment

She has craftily coaxed me to silence as I slip into awe

At any given moment

I see that I am only a small explorer in her noble domain

Because at this very moment

She has painted me a self- portrait of who she is and why she is mighty

Deep Freeze

by Margie O’Loughlin

Today it is bone-chillingly cold

But dogs and their owners are intrepid

So I bundle up for our daily walk

And we head down to the river anyhow

My dog Lola is unaffected by the cold

Though her coat is not luxurious

She has produced a little frost beard this morning

And lifts her paws in a brisk, attractive way

The mighty Mississippi was brown with mud two days ago

But this morning, thick ice reaches from shore to shore

Snow devils whirl and twist across its surface

The ducks and the geese are silent

I throw a stick for Lola, and it hovers in the air

As if it can’t push through

The trees are groaning, the ice is snapping

Lola’s stick finally crashes to the ground

Suddenly wind fills the river valley

In a cheek-puffing exhale of such strength

I think it must have come from the top of the world

Gathering force as it surged across the ice fields of the Arctic

Every now and then someone will ask me how I can stand it here

But I know I will never leave

Like the wind that came to rest in the river valley this morning

This is the place I call home.

Río de Dios (in Spanish)

- Para Chris Stanley

by Sarah Degner Riveros

Hay un río que alegra la ciudad de Dios.

Hay en el río las aguas brillantes que reflejan el cielo urbano.

Hay en la orilla las raíces de los sauces que lamentan y los rizos de los helechos acurrucados al lado del río.

Hay una mano divina que mueve las aguas profundas y turbulentas del Río Mississippi.

Hay una multitud de peces y plantas que fluyen por el agua que los nutre a lo largo del caudal.

Hay en la ribera una manada de niños que gritan y brincan al agua y nos hacen olvidar.

En las profundidades del fondo del río, en la oscuridad, descansa el lodo del cual Dios nos formó.

Hay en el puente una madre que llora, y un hijo gimiendo

Quédate con nosotros porque ya está de noche, y las aguas son profundas y oscuras.

Hay un río que se acongoja con la ciudad de Dios.

Hay en la ciudad un río de Dios.

Hay un río.

¡Ay, Dios!

River of God (in English)

- For Chris Stanley

by Sarah Degner Riveros

There is a river whose streams make glad the city of God.

There in the river are sparkling waters that reflect the urban sky.

There on the shore, the roots of the willows lament and the curls of ferns cuddle beside the river.

There is a divine hand that moves the deep and turbulent waters of the River Mississippi.

There are a multitude of fish and plants that feed among the waters that nourish them all along the river's flow.

On the river bank, a handful of children shout and jump in the water and they make us forget.

In the depths of the river bottom, the mud from which God formed us is resting.

There is a bridge where a mother cries and a son is groaning.

Stay with us for now it is night and the waters are deep and dark.

There is a river that grieves with the city of God.

There in the city is a river of God.

There is a river.

Oh, dear God. ¡Ay, Dios!

The Water Wheel

by Johannah Bomster

Snow, ice, water.

Winter, then snowmelt runoff and Spring rains.

Geese. They mate for life.

Eggs, goslings, geese.

The wheel. The wheel. The wheel.

Staying

by Cecelia Watkins

staying.

what does it feel like?

tell me, old battered willow is it

easier when you’ve no choice in the matter?

is it as simple as a single decision

or must it be an active choosing

an every day re-committing

while knowing the rest of the world

spins on, enchanting, tantalizing

within easy reach…

all it would take is to lift the foot

and go.

the river is a trickster teacher.

at a glance she is a constant, steady

yet the water does not stay.

and still somehow the moving flow it

makes a home, it curves out cozy

hollowed banks and builds a nest

of dogwood, red

as hearts on valentines.

can one live fully without going?

ask the willow.

can one love fully without staying?

ask the river.

Get Them To The River

by Cecelia Watkins

we must get them to the river.

all else can be abandoned.

leave behind curriculae,

all plans, intentions, adult inventions

just step aside with open arms

and watch:

children run to running water.

mussel shells and beaver pelt

life must be smelled, it must be felt!

let us all circle Cottonwood

and ask, how many of us could

hold her in a hug?

how many has she held

throughout her flood-ecstatic

steady life?

the beach is rife with rocks to skip

yes pick one up and throw just so—

these eager little humans pitch

the stones like playground balls

and though they fall straight to the depths

the splashing plunk still makes them laugh.

when time is running short we ditch

all our spreadsheet laid out stations

when you are 10 you have no patience

to wait and watch

to sit and listen

we must let them reach the river.

The Eldest Daughter Questions Mississippi, The Father of Waters

by Willow Thompson

Father, will you play with me?

.......Daughter, you might not have noticed, but I am playing constantly--jumping, rolling, making waves, becoming quiet for no reason. Just waiting for you to join me!

Father, what was it like when you were very young?

.......Daughter, I'll explain it to you some day. Time is a mystery. I come from humble beginnings, but many streams have joined me, many storms have watered me, and many winter squalls have slowed my progress. My job is just to observe and keep moving.

Father, were you always so handsome?

.......Daughter, I'm just who I am. It's only through your eyes that I seem great, eternal, or wise.

Father, when you leave, will you take me with you?

.......Daughter, I never know where I might rest, but every time you visit and enjoy my company, I am giving you knowledge that will help you follow your own path.

Father, I'm getting very busy...I may not be able to visit you for a long time.

.......Daughter, you're an adult now. You have many obligations. Take them on wholeheartedly. Just remember I will always be here for you whenever you need me. Don't be afraid if I seem distant. I'll always have a place for you to rest.

Father? Father?

.......[It's winter now. All is silent.]

Father? I'm alone. I'm scared. Please speak to me.

.......[The trees are bare, the woods are quiet. The animals are gone or sleeping in secret places. The River is still and its surface is white with deep blue ice where it passes near the Daughter's home.]

.......[from a Great Distance: My daughter, I love you. Please think of me in the springtime when the new birds sing. Visit me in summer- it will be warmer then, and even if we don't speak, we can still sit together and share a silence. Come to me in October, when the trees rain golden leaves and the shortened days still leave time for remembrance. Even in winter, I will always be here in some form, until it is time for me to slow down long enough to bring a boat... to show you the way home.

Lost and Found

by Justin Florey

On Father’s Day, I took my older boy down to where Minnehaha Creek flows into the Mississippi River. We parked our bikes by some bushes where the path eroded away into sand. My son wanted to look for lost fishing lures to place in the little tackle box I had given him. He carried it everywhere, even to his weekly appointment with the counselor who was altogether befuddled by his ramblings about Mepps spinners and Mister Twisters. The tackle box was almost filled to capacity and he was already pestering me for a larger one. It perturbed me that every gift seemed to somehow necessitate another.

“Just be satisfied with what you have,” I told him which was something I was forever telling myself.

The bank was crowded with people angling and throwing rocks. A festive procession crossed the footbridge to follow the creek back up to the waterfall. The creek was a foot lower than the last time we had been there catching bluegills from the bridge. Now the water was too fast and low for that. I commented to him how the river was a little different each time. I pointed out the island out towards the dam, how sometimes it was underwater with just the trees visible. I told him we’d canoe out to it someday and fish. He seemed a bit lost as to where to begin his search. I suggested he try looking in the exposed roots of a dead tree that usually held fish when the water was up. He managed to find a few jigs and a bobber but seemed disappointed.

“Well, you can keep on looking if want or help me pick up trash,” I said raising the Hefty bag I had brought along.

We split off in opposite directions. I stooped over to place the discarded energy drink cans, plastic water bottles, bait containers, broken beer bottles, soggy diapers, and whatever other manner of American detritus I could find into the sack. It was sickening to me that people treated the shoreline of what I considered a national treasure with such contempt. Almost unavoidably, when I told anyone I liked to fish there for walleye and smallmouth, they were surprised that anything other than a carp could live in such a polluted sewer. Well, I wouldn’t drink out of it, but it did support an incredible abundance of life--birds especially. I almost always spied a bald eagle or a heron whenever I went there. As I like to tell my boys, “If you throw a worm into the Mississippi, you never know what you might catch.”

I turned my attention to an accumulation of bottle glass along the concrete wall of a graffiti-covered storm drain. Drunken hooligans had tossed their empties down from above. I smiled apologetically for intruding on a Spanish-speaking family fishing nearby. Pausing in my collection, I looked around for Miles but couldn’t see him. I hurriedly gathered the rest of the trash along the wall and went back toward the bridge. The bag was heavy now and I was eager to dispose of it. Finally, I picked him out of the crowd by his bicycle helmet. Moving along the shore, he looked like a walking mushroom as he scanned the river-stones for treasure.

I paused near the dead tree where a man was staring intently into the water as he repeated the same short cast with a plastic worm. Utilizing my polarized sunglasses, I could make out a pike undulating in place like an eel in the creek current. I reached Miles and showed him all the trash I had collected. He grumpily showed me a hook he had found.

“That’s a good catfish hook,” I told him. “Should we get back home? You seem tired and I don’t want to keep you out here too late.”

“No,” he snapped. “I’ve barely found anything. I’m still looking.”

“All right, a little longer. Look son, people don’t want to lose their fishing lures.They’re expensive. You just have to find them by accident when you fish. If you go out looking for them it won’t happen. That’s how it works. Why don’t you look in those rocks?”

Riprap lined the shore all the way to the lock and dam. I watched him balance nimbly on the boulders and concrete slabs. He had become a boy, determined with his own interests. I cautioned him to be careful. My son possesses a great innocence and sensitivity, an openness to new experience that will unavoidably dull over time. People will make him ashamed of these qualities and he will learn to disguise them from the world. He will be corrupted. He will grow up. I cannot stop this from happening, nor would I want to. I can only recognize this moment we inhabit together as special.

“Try looking under the rocks where people might have gotten snagged. The best time to try would be right after the water level drops. I’m going to get those plastic bottles up there and then we’re going to leave. We need to get you into bed.”

We scrambled up the bank. I placed the bag of trash into a barrel and went to the spot I had left the bikes. I looked down at the blank area of grass a bit startled and confused.

“We left them somewhere around here,” I said turning my head about wildly as I walked in a circle.

“Our bikes were stolen,” my son stated in a flat, dejected way.

I felt gutted, like something had been carved out of me from my throat to my solar plexus. I placed my hand on my son’s small shoulder.

“I’m sorry this happened. This is Dad’s fault.” I looked around at the laughing people feeling altogether violated and stupid. “I should have locked them up.” I looked into my son’s face. He was calmer than I would have expected, in shock I suppose. “We’ll have to walk home.”

I was relieved he was taking it so well. Two miles would have been a long way to carry him. I took out my phone then put it away. I was quite worried about what my wife would say. We walked quickly down the gravel path, both of us angry in our strides.

“Maybe we can catch up to them,” I said even though this was absurd given they had bikes and we didn’t. We both had our helmets on. God, I felt like a fool! “You might get to see Dad kick someone’s ass,” I muttered.

I was angry with myself. I had that mountain bike since 1995. It was a damn good bike. I thought of all the miles I’d rode on it. Then an image of my son standing confidently on the pedals of his own bike formed before my eyes. On the way there, I had been so proud of how well he rode. He’d started out the season on training wheels, reverting to them after a bad experience. The bike had been a little big for him before. It was his first bike. I had given it to him for his birthday. Now it was gone. What kind of a sociopath steals a father and son’s bicycles on Father’s Day? I realized that I had become overly comfortable, living in some imagined bubble. There were rapists and murderers living in Minneapolis. I had to do a better job looking out for my son. I stopped walking and rubbed his back, asking him if he was ok.

“I want my bike back,” he declared angrily.

“Look, we’ll get you a new bike. This is Dad’s fault. This isn’t your fault.”

“Can I get a mountain bike?” he asked, perking up.

“Maybe, I have to talk to Mom. Money’s a little tight right now. We’ll take care of you. You’re gonna have a bike.” We started walking again. “I just want you to remember how this made you feel. That’s why we never steal from anyone, because this is how it makes them feel.”

He furrowed his brow and nodded in deep understanding.

“You saw all those people down there. Most people are good. But a small number of bad ones ruin it for everyone else.”

He nodded again. I texted my wife the unfortunate news. We came to a pool where kids like to wade with a large family gathering nearby. I looked for our bikes amongst the crowd of picnickers. Internally, I continued to beat myself up. The evening before Miles had complained about being bored and I suggested we hang the birdhouse that had been in the basement since winter.

The ground was a bit uneven and the footing on the small stepladder wobbled under me as I strained to fasten the birdhouse to the limb with a length of rope. To make him feel involved, I asked him to hold the ladder. I immediately realized this was stupid, but blundered ahead anyway. The rope slipped and I saw the house strike the top of his head and the bright red blood on his shirt.

“Oh, my God!” I exclaimed and ran for a towel.

It looked worse than it was, a small cut in his scalp that didn’t require stitches. We got it to stop bleeding. I’d started my second beer before this happened. I was always scrambling to meet the demands of my family. I barely had time to take a shower, let alone sit down when I came home from work. I needed things to stop moving so fast, but I knew they never would. We had left the river area and came to the playground. I wanted to check the bike racks by the waterfall in case someone had just taken them for a joyride. It was a slim chance, but I wasn’t ready yet to let go. Miles had been complaining about his legs being tired. I asked if it would be all right to leave him.

“I don’t want to lose you too,” I said.

I jogged down to the falls and, of course, found nothing, many bikes but none of them ours. I hurried back to Miles. We checked at the Dairy Queen because, as I said to him, “criminals tend not to be the brightest people.” Walking along the sidewalk of Minnehaha Avenue, I noticed someone walking a bike with someone else riding a block ahead. It looked like a children’s bike.

“Those could be our bikes,” I said to Miles.

I started running. Miles started running too. They weren’t our bikes which was probably just as well. I felt like a 12-year-old. It was time I got my son home. Bike-less, we said hello to the neighbors without explaining what had happened and put our helmets in the garage. He started crying when he got inside the house. After we’d finally got him settled down, I saw him throwing punches in the air inside the shower.

A couple of days later, Emily found a children’s mountain bike at a good price on Craigslist. I drove Miles to Roseville and we checked it out. It was black with gears and a suspension fork. Miles loved it. I had been concerned about him using a handbrake. He didn’t have any problems. My first bike had been a red Schwinn with a banana seat. It had a horn and a bell. My parents made me put a flag on it. When I got to be school-age I realized I should have bought a dirt bike like the cool kids. Driving home with the knobby-tired bike in the trunk, I felt redeemed.

“This is kind of an upgrade,” Miles said happily from the backseat.

The next evening, I took him on some flat trails that meandered through the trees along the Minnesota River. He tried to go through the first puddle he saw and got stuck in the mud.

“You have to go around the big puddles here,” I said. “You better follow me.”

With his low center of gravity and fearlessness, he was a natural, cruising over obstacles that I didn’t even attempt with the narrow tires of my wife’s bike. It had been years since I had been on that trail.

“I love mountain biking!” he cried out in exuberance more than once. Both him and his bike were covered in mud. He could ride as fast as me.

“If you’re doing this at 7, think what you’ll be doing at 17.” I told him. “Dad won’t be able to keep up with you.”

“Yeah!” he cried.

“Dad will be old then,” I said too quiet for him to hear. “Dad’s old now.”