Ribbons of habitat for water quality: Buffers proposal offers new hope for an old problem

Strutting along the edge of a cornfield on an autumn morning, a large coppery bird with dark iridescent head, white collar and red eye-patches bursts into flight with a quick drum roll of wings, long tail feathers waving behind with cocky panache.

It’s not the image that comes foremost to mind when thinking about healthy streams and rivers; but the ring-necked pheasant has recently become an unwitting and unlikely poster child for efforts to improve water quality in the Land of 10,000 Lakes.

Earlier this year, Governor Mark Dayton proposed an initiative requiring vegetated buffers along all waters of the state. The governor’s announcement made at an annual DNR-sponsored gathering of hunting and fishing stakeholders, grew out of a December summit Dayton called to address the state’s declining pheasant population. A coalition of 29 environmental and conservation organizations – including Friends of the Mississippi River – promptly sent letters to Dayton praising his buffer proposal. “Expanding the practice of shoreland buffers presents an enormous opportunity to improve water quality and the state’s natural resources,” they wrote. “These buffers provide a way to decrease nonpoint source water pollution while creating corridors of habitat for wildlife.” Since then, FMR has been working diligently with state officials to craft legislation putting the governor’s proposal into law.

What began with hunters looking for ways to help a popular game species is now being heralded as one of the most significant water quality initiatives put forward by a Minnesota governor in decades.

Buffer basics

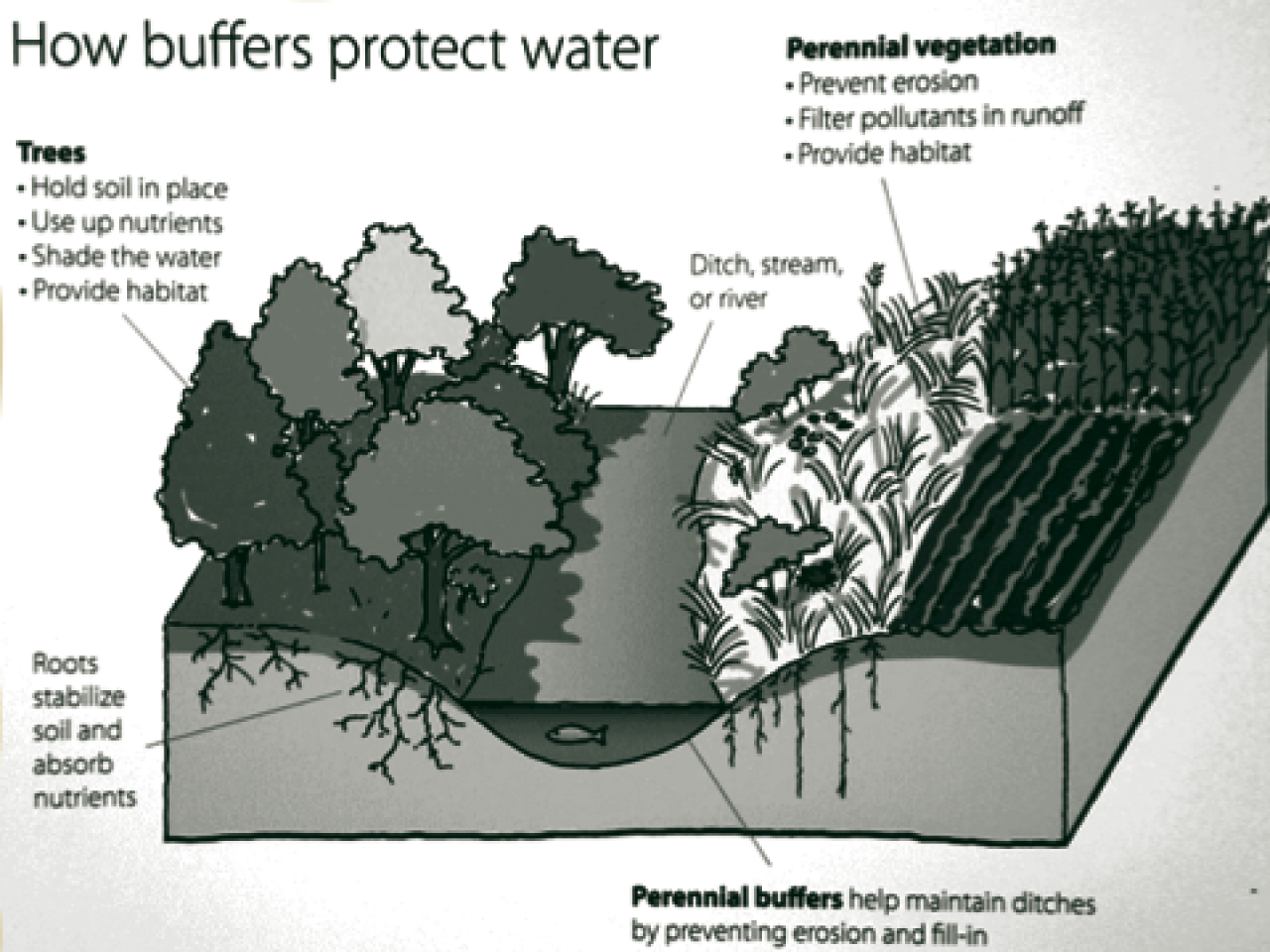

A buffer is a strip of uncultivated land that lies between a farm field and a body of water. Rather than planting crops right up to the stream bank or shoreline, where a swath of perennial plants such as grass and trees are allowed to grow. This ribbon of permanent vegetation along the water’s edge provides habitat for numerous species, from butterflies and pollinators to frogs, songbirds and – yes – game species such as pheasants.

Where buffers really pay dividends is by improving water quality. When precipitation runs off farm fields, it can carry a stew of nasty substances that don’t belong in the water. Nitrates and phosphorus from fertilizers promote algae blooms and cause the infamous Gulf of Mexico dead zone. Soil is washed off cultivated fields and turns lakes and streams murky and pathogens from livestock manure get swept downstream.

A successful grass buffer in Redwood County

Photo: BWSR/Redwood SWCD

The Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), a federal agency that works with farmers, estimates that vegetated buffer strips can remove or intercept 50% or more of the nutrients and pesticides in runoff, 60% or more of some pathogens, and 75% or more of sediment. The deep roots of the native plants are preferred for buffers to help stabilize stream banks and reduce erosion, while also promoting the infiltration of rain into the soil.

Habitat corridors, cleaner water, stream bank stabilization, and healthier fisheries – a combination of benefits that the NRCS refers to simply as “Common Sense Conservation.”

New emphasis on an old idea

The idea of perennial vegetation along waterways isn’t new. Starting in 2000, FMR launched a program to help landowners plant native grasses, forbs and trees along the Vermillion River and its tributaries. FMR subsequently pushed for proactive buffer requirements throughout the Vermillion River watershed. The group also successfully led the push for a statewide Shoreland Buffers program that provided financial and technical assistance to landowners from the Board of Water and Soil Resources (BWSR).

Tim Koehler, senior programs advisor for BWSR, notes the concept has been around for a century, and the use of riparian buffers has been actively promoted through state and federal conservation programs for more than 30 years. Since 1989, Minnesota rules have required a 50-foot buffer in agricultural areas along all public watercourses on the “Public Waters Inventory.” That list, however, doesn’t include every basin with standing or flowing water.

Another part of state law requires a 16.5-foor buffer along drainage ditches, but only when certain conditions are met. According to BWSR’s Koehler, only 20% of drainage ditches in the state fall under that requirement. The two laws together apply to only about 36% of the watercourses in Minnesota, leaving nearly two-thirds unprotected. On top of that, enforcement of the rules, which is delegated to counties, is spotty to nonexistent. According to the state, only 6 of Minnesota’s 87 counties are fully enforcing the 50-foot shoreland ag buffer. Other sources indicate only about half a dozen counties have undertaken a thorough review of where buffers are required and followed up with landowners who are not in compliance.

The governor’s proposal would address both deficiencies, requiring permanently vegetated buffers along most waters, and providing for stronger state oversight of enforcement.

Farm country in the big city

Why, one might ask, should an organization focused on the Mississippi River as it flows through the seven-county Twin Cities metro region care about what a farmer does hours away in Watonwan County? FMR’s water programs director, Trevor Russell, answers that question in three words: the Minnesota River. The state’s namesake river drains water from nearly 17,000 square miles of some of the richest, most intensely farmed land anywhere, water that carries tons of sediment and a steady stream of phosphorus and nitrogen from agricultural runoff, discharging it all into the Mississippi a few miles downstream of Minnehaha Park at Fort Snelling.

“The largest share of sediment, nitrates and phosphorus pollution in the Mississippi River is coming from the Minnesota River basin,” Russell says. “We can’t achieve water quality standards in the Mississippi until we address agricultural pollution in the Minnesota.”

While some of the issues around agricultural pollution stem from federal farm policy, a topic on which the state has little say, promoting the use of riparian buffers is something the state can do to make a difference, says Jeff Strock. A professor and soil scientist at the University of Minnesota’s Southwest Research Center in Lamberton, Strock has seen firsthand the water quality benefits that can result from different approaches to land management and crop production. Riparian buffers are just one practice in a toolbox that also includes alternative designs for drainage ditches, different methods of tillage, restoring wetlands, planting different crops, and more precisely tailoring the amount of fertilizer to what crops need. No one technique alone is sufficient to address nonpoint agricultural pollution.

“It’s going to take all of these things to meet water quality standards,” Strock says. “One size doesn’t fit all, and there isn’t any silver bullet.” It’s not just a matter of asking farmers to change their production methods or the crops they plant. Some of the monocultural corn production in the Minnesota River watershed is fueled by the demand for livestock feed and Americans’ appetite for meat. We may need to examine our own habits as well as those of farmers.

“These are really complex and interconnected systems,” he says. “There are a lot of different changes that have to happen, from producers to consumers.”

Reasonable expectations

Both Strock and BWSR’s Tim Koehler are quick to point out requiring riparian buffers in agricultural areas may mean transitioning some land from annual to perennial crops. They also acknowledge water pollution has costs as well. The question boils down to who pays for what, and what is reasonable.

Recent analysis by the Environmental Working Group found riparian buffers in Iowa could go a long way toward achieving that state’s water quality goals while having minimal impact on farmers. In the five Iowa counties examined, they found only 11% of farmers would be affected by requiring a 50-foot buffer, and 71% of those would only need to convert an acre or less of cropland to perennial cover – leading the group to refer to buffer requirements as “low-hanging fruit” – something relatively easy and inexpensive to implement, but paying big dividends in terms of water quality. FMR executive director Whitney Clark thinks that’s even more so here in the state where the Father of Waters starts its long journey south.

“Governor Dayton deserves praise for putting forward a proposal that’s bold but pragmatic,” Clark says. “Requiring a baseline of care for the land in relation to water quality is a reasonable expectation that everyone ought to be able to get behind. It’s a real opportunity to make major progress on what’s been an intractable problem.”