Nitrate in drinking water

Nitrate is essential to plant growth and animal health, but excess nitrate in our drinking water can pose risks to human health. FMR supports a groundbreaking strategy to safeguard the river and drinking water while strengthening rural economies.

Nitrate in drinking water: An overview

Nitrate (NO₃⁻) is a compound of nitrogen and oxygen that occurs naturally and is produced from human activities. It is highly soluble in water and often used in fertilizers for crops and lawns, but that also makes it a common groundwater contaminant. Nitrate contamination most often affects people in small towns who rely on community water systems or private wells. You cannot taste, smell or see nitrate in water.

Once a water source becomes contaminated, protecting people from nitrate exposure can be costly. Conventional drinking water treatment processes do not remove nitrate, so additional — and often expensive — treatment systems are required.

Health standards and impacts

Consuming too much nitrate can interfere with the blood’s ability to carry oxygen and may cause ‘blue-baby syndrome’ (infant methemoglobinemia), which can lead to serious illness or death. To protect us from health hazards, EPA set a maximum contaminant level (MCL) for nitrate10 parts per million (10 mg/L).

Beyond ‘blue-baby syndrome’, the harmful health effects of nitrate in drinking water are still being studied. The current EPA standard or maximum contaminant level (MCL) does not take into consideration potential connections to colorectal cancer, thyroid disease, and neural tube defects (birth defects of the brain and spine). The State of Minnesota considers the connection between nitrates and thyroid issues, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and cancers worthy of additional research.

The impacts of excessive nitrate also go beyond potential health concerns. Elevated nitrate levels can harm fish and aquatic life in our lakes and streams.

This is why EPA is involved in areas especially prone to nitrate pollution, like southeastern Minnesota. And some state agencies, like the Minnesota Department of Agriculture and Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, have been ordered to work together to reduce nitrates in drinking water.

To learn more about public health concerns, see the Minnesota Department of Health’s information sheet Nitrate and Methemoglobinemia (PDF) and this article on Safe Drinking Water for Your Baby.

A groundbreaking strategy to cut excess nitrate in drinking water: Winter-hardy oilseeds

A 2023 report identified winter-hardy camelina (pictured above) and domesticated pennycress as powerful engines for a healthier environment and economy, forecasting up to 5.5 million acres of these winter annual oilseeds in Minnesota by 2050. Both produce oil that can be converted into renewable diesel and jet fuel with significantly lower life cycle GHG emissions. Research shows camelina-based jet fuel, compared to petroleum-based jet fuel, can reduce GHG emissions by more than 60%. Companies from across the agriculture and energy sectors are making major investments to meet this demand for low-carbon fuels. (Photo by Dodd Demas)

Nitrate in drinking water is a widespread problem in Minnesota, particularly in the southwest, west-central, and southeast karst region (where the EPA indicated action was needed to protect public health in 2023). According to a 2020 report, one in eight Minnesotans relies on groundwater with elevated nitrate levels.

In Minnesota, more than 70% of nitrate loads in monitored watersheds come from cropland.

Growing winter-hardy oilseeds such as winter camelina and pennycress could help reduce nitrate runoff from agriculture.

Winter oilseeds and other Continuous Living Cover (CLC) crops keep living roots in the ground through the “brown months” between late fall and spring when Minnesota’s croplands lie bare.

According to a 2023 report, a realistic statewide rollout of Continuous Living Cover (CLC) in Minnesota could lead to a 23% reduction in nitrogen runoff.

Because winter oilseeds can be used in Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF), they can also provide a new revenue stream for farmers without replacing summer crops.

Reducing the amount of nitrate that Minnesota cities need to remove from their drinking water also reduces their financial burden. (Nitrate removal is expensive. The city of Hastings is requesting millions in state funds in 2026 for plants to remove nitrates as well as PFAS from city drinking water.)

How you can support this win-win solution

Planting winter oilseeds between cash crops addresses nitrate pollution at its primary source — safeguarding communities while opening new income streams for farmers.

If you would like to sign action alerts supporting continued investment in these important crops and programs, join the FMR River Guardians.

If you are a farmer, learn more about winter camelina from the Forever Green Initiative at the University of Minnesota.

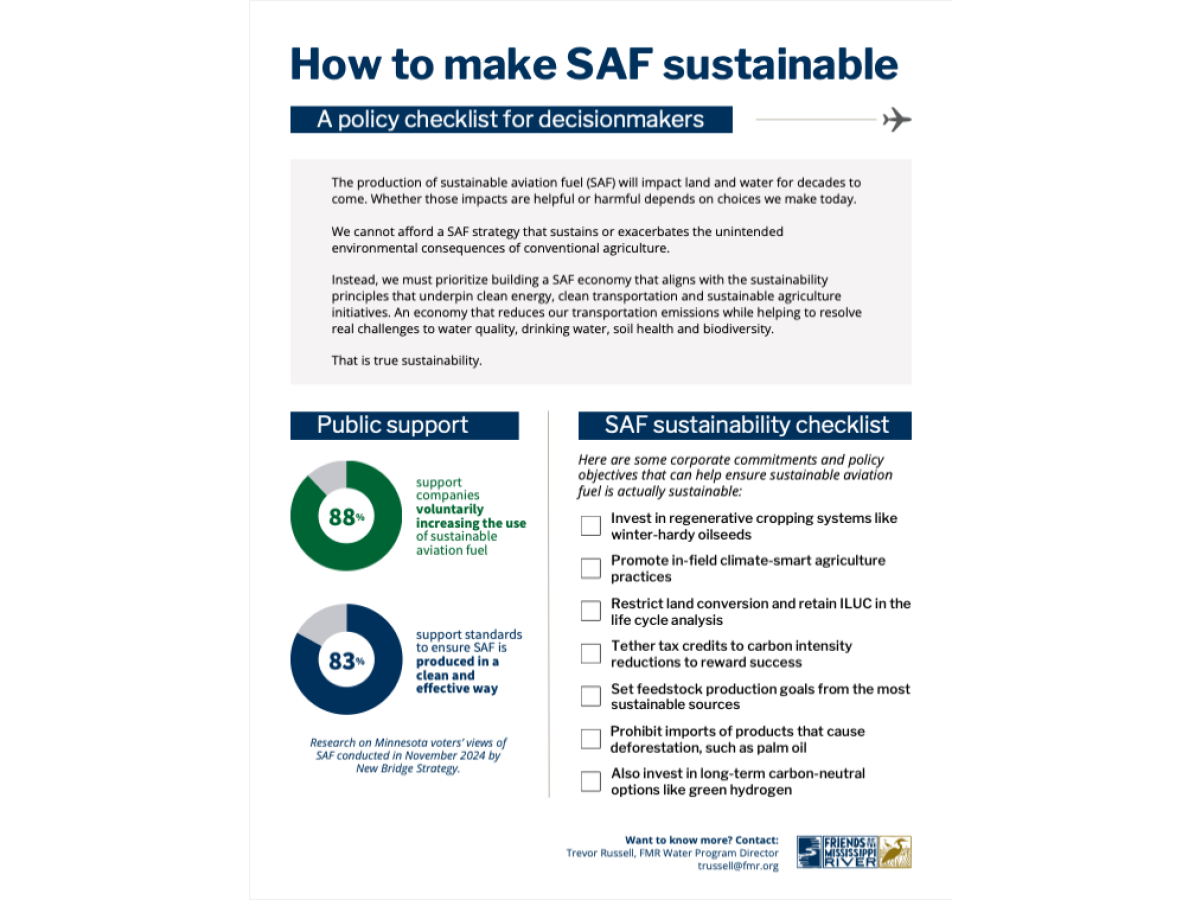

If you are a business or researcher involved in SAF, download the printable checklist below to ensure your sustainable aviation fuel is truly sustainable.