The case for and against lock and dam removal

The question of lock and dam removal is a big one. In general, dam removal is good for rivers; it rejoins fragmented ecosystems and improves water quality. But we don't yet know the specific costs and benefits of removing the two locks and dams in the Twin Cities currently under consideration.

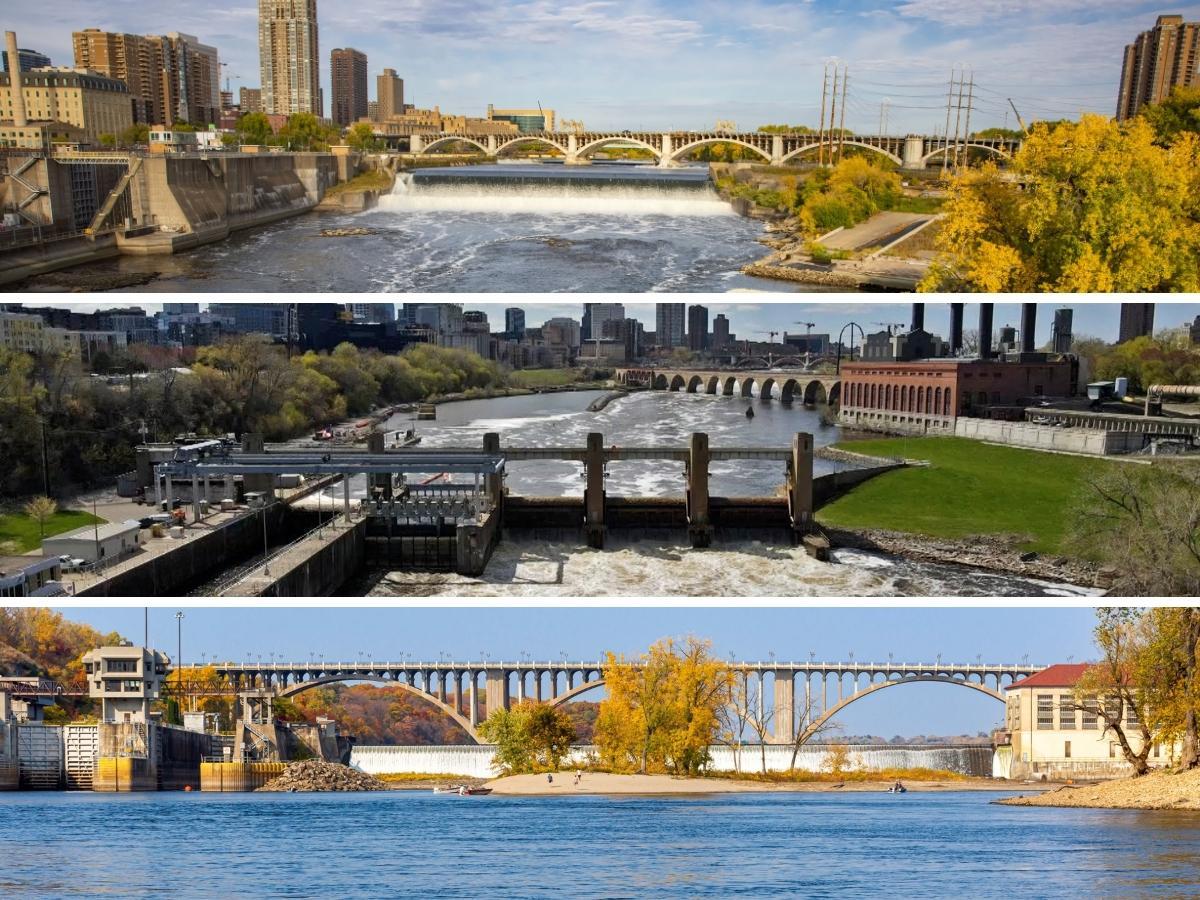

Removing Lower St. Anthony Falls lock and dam and Lock and Dam 1 (the Ford Dam) would reconnect 39 miles of river through the Mississippi's only gorge right here in the heart of the Twin Cities. (Learn why Upper St. Anthony Falls lock and dam should not be removed.)

Is dam removal the best scenario for our metro river? This would be the first urban dam removal project at such a large scale — an exciting prospect, but an expensive one with potential drawbacks. Here are some of the questions we need to consider together.

What wildlife species might benefit from dam removal and gorge restoration?

Dams segment rivers that used to flow freely. That segmentation disconnects the long stretches of river needed for many fish to spawn (reproduce). The reservoirs created by dams also eliminate habitats where these fish spawn.

But if we remove the dams, we have a chance to reconnect the river and restore floodplains and big-river rapids, an important habitat type that no longer exists on the Mississippi.

American Rivers has identified over 50 rare, threatened or endangered species that could benefit from dam removal including fish, mussels, mammals, reptiles, insects and plants.

Many more fish species used to use this part of the river. Right now the biodiversity is low; there are maybe 20 species of fish in the gorge versus the 125 that used to live here. Many fish, including paddlefish and sturgeon, used to spawn in the rapids here. Those species have returned to other Minnesota rivers where dams have been removed.

Those fish are hosts for mussel species that clean the water and serve as a food source for other animals. Of course, cleaner water supports other species, and so on. Dam removal has the potential to restore a vital, intricate ecosystem.

Dam removal could usher the return of river giants like the paddlefish. (Photo credit: Ryan Hagerty/USFWS)

Would dam removal increase the spread of invasive carp?

That's one element of dam removal that would need careful consideration. The Upper St. Anthony Falls lock and dam (not under consideration for removal) block invasive carp from reaching the Mississippi headwaters. But the threat to the waterways below the falls is still very serious. Carp have been moving their way upstream for decades. As far as we know, there isn't a large population of them in this part of the river yet, and they aren't reproducing here. Right now, the more urgent threat is in southern Minnesota.

Regardless of whether we remove Lower St. Anthony Falls lock and dam or Lock and Dam 1, we need barriers and other prevention activities further downstream in southern Minnesota. If they reach the metro stretch of the river, invasive carp will have already infested the St. Croix River, the Minnesota River, Lake Pepin and other treasured waterways. It will be too late.

That's why FMR has been a leader in protecting Minnesota's rivers from invasive carp, including by securing funding for an invasive carp deterrent much further downstream at Lock and Dam 5.

Dam removal might help the river become more resistant to takeover by carp who do make their way upstream. Healthy river habitats with strong native fish populations are more resilient to invasive species and foster more predators for invasive carp. So the best strategy against the spread of invasive carp might be a combination of tactics: proven barrier technologies in place at downstream locks and dams where they will be most effective, as well as a healthier habitat here that can withstand any damage from carp that do slip past the downstream barriers.

The dams currently generate hydropower. What would dam removal mean for energy?

Currently, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers owns both the lock and dam at Lower St. Anthony Falls. Brookfield Energy leases the hydropower generation rights for the dam. The Corps also owns Lock and Dam 1. Brookfield Energy leases the hydropower generation rights for that dam as well, which originally powered the nearby Ford Motor Company assembly plant.

Hydropower is a carbon-free energy source, but it isn't entirely "green" because hydro dams are so harmful to rivers. Together, the two dams being considered for removal produce a maximum of 26 megawatts of power a year (dependent on river flow levels). Continued advances in renewable energy technologies could mean that there are other options for generating this amount of power should the dams be removed.

Would an undammed river affect our bridges, other infrastructure and parks?

This is another question that needs more study. Bridges, storm drain outflows, retaining walls and other structures have been built around the river as it currently flows. (Some bridges in the gorge predate the locks and dams, some were built after the dams.) Dam removal would change water levels, flows and scour patterns, all of which could impact surrounding infrastructure. We need to know how that infrastructure could be adapted for a changed river and what that would cost.

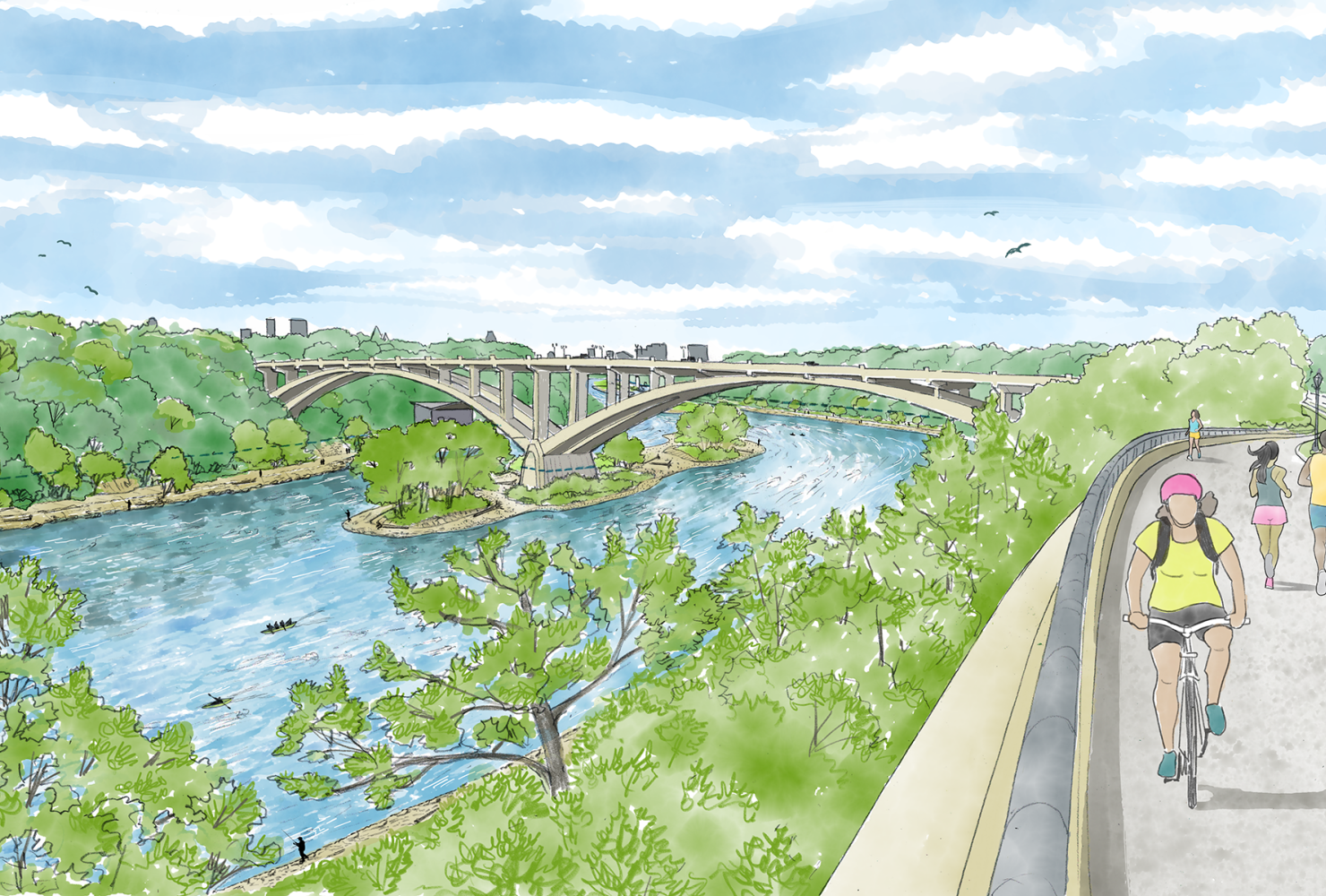

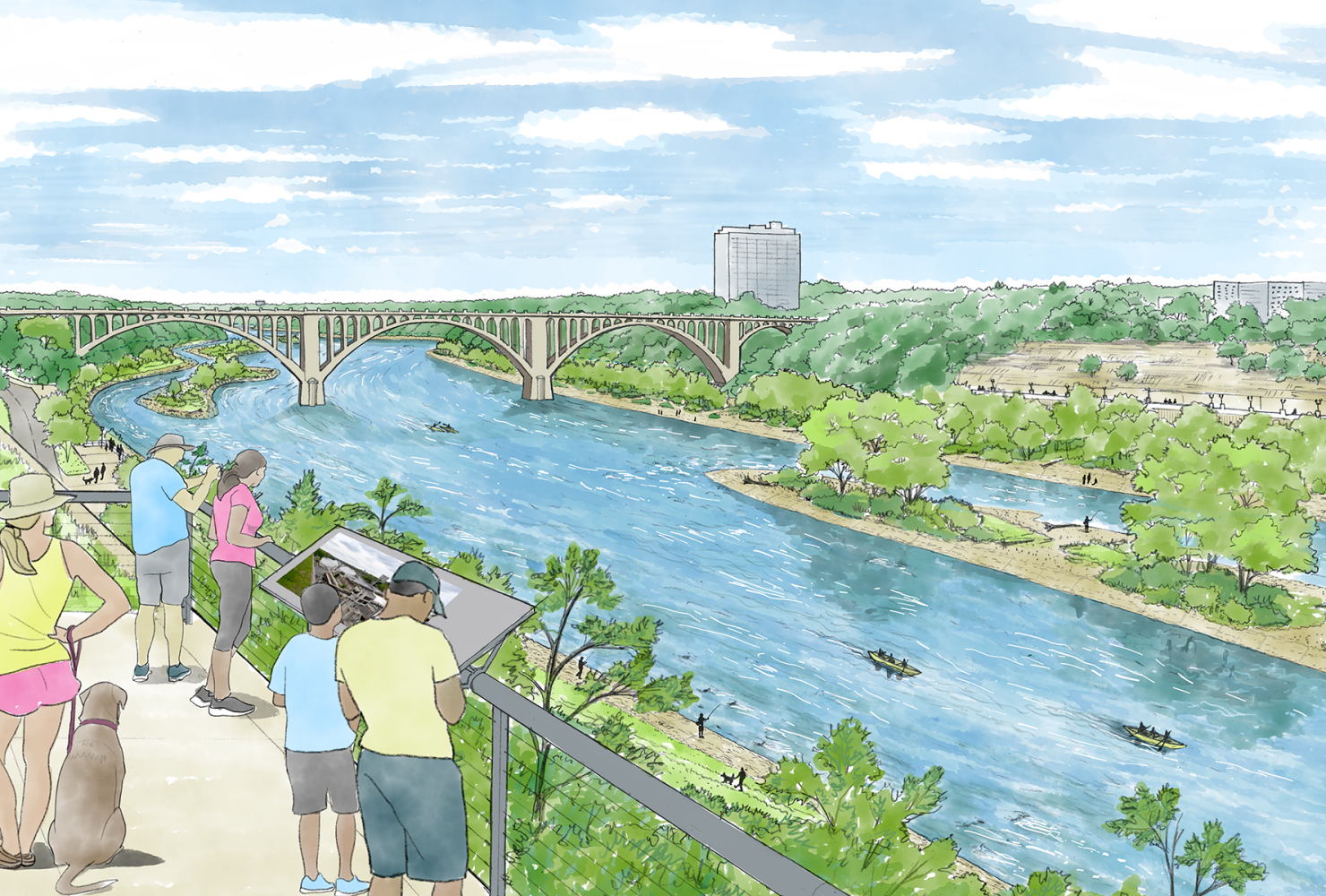

Dam removal would also expose more shoreline and islands in the river gorge. This land would be primarily public parkland for Minneapolis and St. Paul to manage, as most of the existing shore areas are publicly owned. New park areas (and changing riverfront recreational opportunities) might call for new trails and recreational facilities.

If dams were removed, beloved parks like the Mississippi Gorge Regional Park might gain shoreline as the water level shifts. (Photo by Jim Hudak)

Would the river flood more if the dams were removed?

No. These locks and dams don't provide flood control right now. Water levels in the gorge would vary more, but flooding wouldn't be any more likely than it is now. Much of the time, water levels would be lower than they are now because the dams are holding back and pooling water.

Water levels downstream of Lock and Dam 1 (including in downtown St. Paul) would not be affected; that water level is managed by Lock and Dam 2 in Hastings.

Could river sediment stored behind the dam walls be released if the structures were removed? What would that mean?

Lock and Dam 1 might currently be holding back about three million cubic meters of sediment: sand, dirt and other material that would normally be washing downriver over the course of time. The Lower St. Anthony Falls dam also holds back some sediment. Releasing all of this sediment at once would cause problems downstream in an area of the river that already requires more dredging than most. The sediment would need to be removed before we remove any structures.

We also don't know whether the sediment is contaminated with toxic substances. We hope to see both of these questions rigorously examined in the Corps' study.

How would recreation change on an undammed river?

Without dams, this section of the river would be shallower with more variable flow velocities. Water levels would fluctuate with the seasons, as they do now but at a lower elevation and the way we'd use the river for recreation would change. There might be more opportunities for shore fishing, paddling (including a short section of whitewater paddling when water levels are high) and perhaps even tubing (when water levels are low).

However, some of the boaters and rowers who like the current flatwater pool wouldn't have that kind of river anymore. The Minneapolis and University of Minnesota rowing clubs would need to move their operations and facilities up or downstream or to lakes.

Would dam removal be cost-effective?

Removing the dams and restoring the river gorge would be expensive. But it's a one-time cost versus the ongoing cost to maintain the Corps' aging structures. We don't yet know what this project would cost and which parties would pay that cost.

We also need to consider where this fits in the list of community and environmental priorities. We know there are benefits to dam removal, but could we achieve similar benefits in a different way? Would other needs in our community not get enough funding or attention if dam removal were to become a priority? What would happen to efforts to create new parks and river connections in marginalized neighborhoods?

These are the kinds of costs and benefits that we need to carefully consider during this process.

Who can answer these questions?

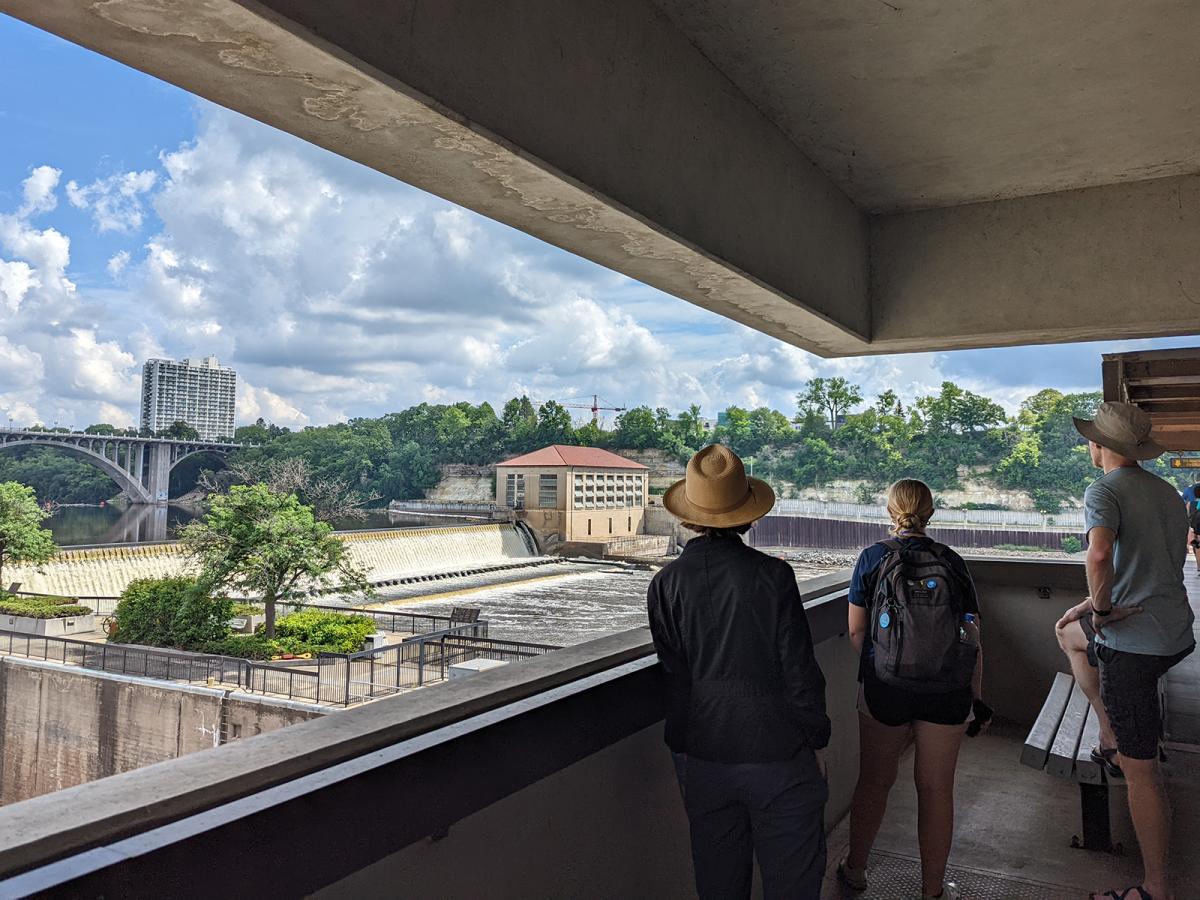

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' disposition study will begin to explore these questions, but it probably won't provide all of the answers we need. FMR and our partners will continue to advocate for more community engagement and more research before we reach any conclusions about whether dam removal is right for our river.

Dam removal is an intriguing possibility, but it needs more examination. FMR believes that together we can best chart a course to protect and restore the health of our river and all the communities and wildlife that depend on it. Read our full position on lock and dam removal.

Learn more and get involved

This process will unfold over many years, and FMR will be involved every step of the way.

We'll host a variety of workshops, tours and events about the future of Twin Cities locks and dams in the coming years. We're also happy to give special presentations to community groups upon request. And we'll be sure to tell our advocates about ways to weigh in and shape the future of our metro river.

Learn about Twin Cities locks and dams, the pros and cons of removal and more here. For additional details, contact FMR Land Use & Planning Program Director Colleen O'Connor Toberman, ctoberman@fmr.org, 651.477.0923. The best way to keep up with the latest news and hear about opportunities to get involved is to sign up as an FMR River Guardian below.

Become a River Guardian

Sign up and we'll email you when important river issues arise. We make it quick and easy to contact decision-makers. River Guardians are also invited to special social hours and other events about legislative and metro river corridor issues.

See a map of our three Twin Cities locks and dams, a timeline of when and why they were built, and find out why we may not need them anymore.

What will happen to metro locks and dams? Here's a rundown of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers disposition study process and timeline, the scenarios under consideration, plus ways you can shape the river's future.

To keep up with the latest developments around this process and hear about how you can weigh in, check out our most recent articles on locks and dams.