Wic̣aḣapi

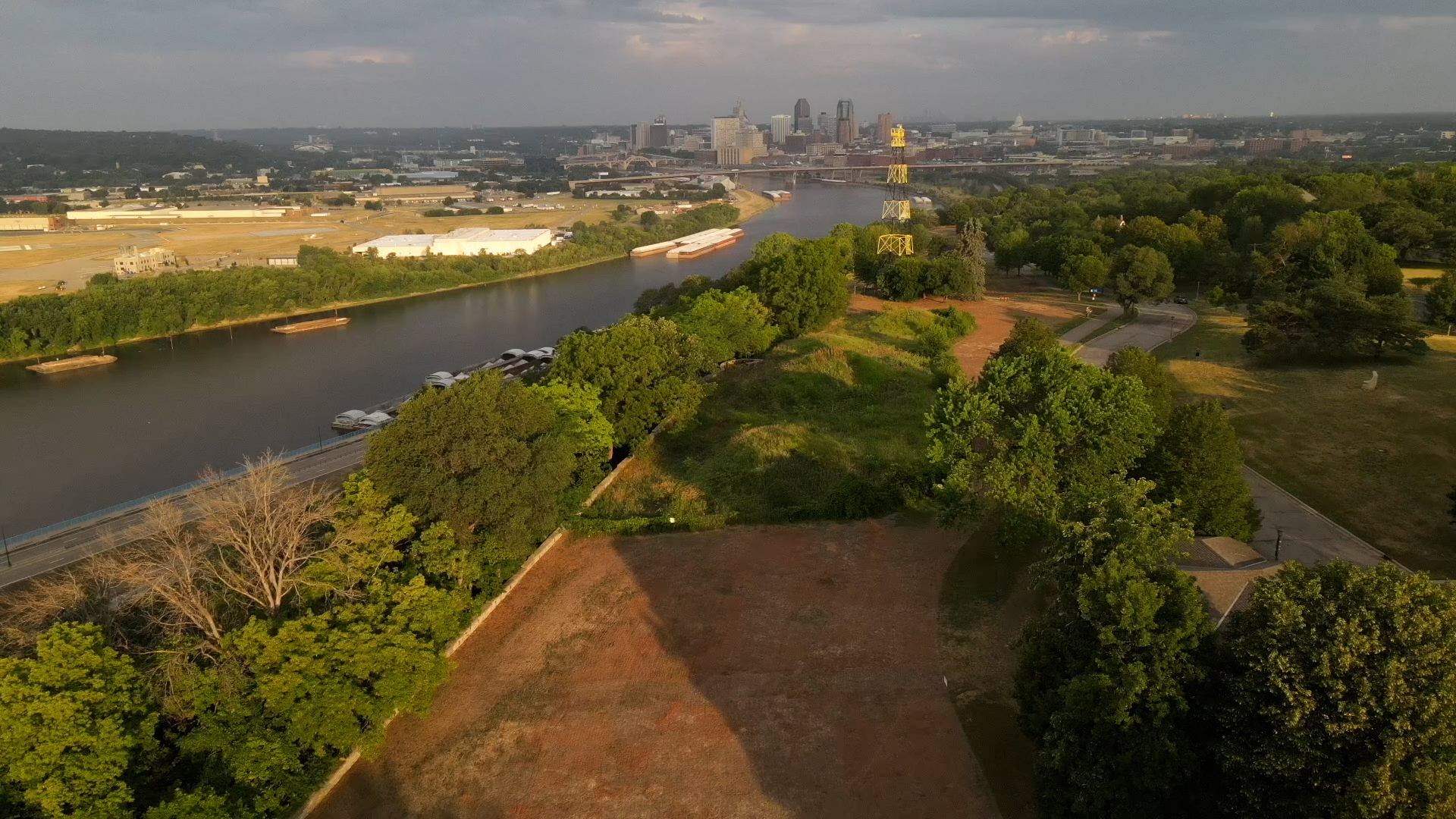

Wic̣aḣapi is a cemetery built by the ancestors of living Indigenous people, home to the only known remaining burial mounds within the Twin Cities core. FMR has helped restore dry prairie and oak savanna at this sacred blufftop place in St. Paul since 2011. (Photo by Mike Durenberger for FMR)

Where is Wic̣aḣapi?

Just east of downtown St. Paul, the 111-acre Wic̣aḣapi (formerly called Indian Mounds Regional Park) extends along the river bluff.

Wic̣aḣapi is part of a vital habitat corridor in East St. Paul. We've restored habitat at nearby Waḳaƞ Ṭípi, which lies just below the bluff, and the DNR's nearby Central Region Headquarters, also referred to as the Willowbrook site. Other close natural areas include Battle Creek Regional Park and Pig's Eye Regional Park.

Our work here takes place on Dakota homelands, and this is a sacred site; if you visit, come with respect.

What's special about Wic̣aḣapi?

Wic̣aḣapi is a cemetery built by ancestors of living people. The place has deep significance to the Upper Sioux Community, Lower Sioux Community, Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community, Prairie Island Indian Community, Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin, Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska, Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate, and other descendants of those who are buried here. It is home to the only known remaining burial mounds within the Minneapolis-Saint Paul urban core.

Six burial mounds remain. The bluff used to hold 50 to 200 mounds, some created more than a thousand years ago, prior to settler-colonial destruction. The mounds on the bluff, the cave below and the riverway make this whole region a sacred place to the Dakota. In large part because of this history and cultural connection, the site is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 2025, the city returned to a Dakota name for this culturally significant place.

Please check out Wakáŋ Tipi Awaŋyaŋkapi's webpage to learn more and watch this playlist:

In the late 1800s, European-Americans flattened mounds to make way for roads, homes and infrastructure for a city park: Indian Mounds Park, one of St. Paul's first parks, established in 1892. A limestone quarry, oak savanna logging and amateur archaeology also destroyed mounds. For many years, institutions and organizations have not represented the full cultural importance of this site to the Dakota and other Indigenous peoples. The City of St. Paul is working with Native nations to change that. The Cultural Landscape Study and Messaging Plan for this park, planned in consultation with Dakota Tribal nations as well as a Project Advisory Team, looks back to the history of the place and plans for better interpretation over a 20-year arc.

One of the first steps included the installation of signs throughout the park that call visitors to respect the place and remember what it is. One sign reads "Táku Wakháŋ Thípi — this is a burial place and our ancestors are still here."

Today, people continue to visit this place because of its cultural significance and its beauty — from the blufftop, you can see the sweep of the Mississippi River and downtown St. Paul. It's clear from the view: One city park is only part of this place. Linking and improving the health of the land along the river contributes to the crucial migration corridor of the Mississippi River flyway and increases habitat and climate resiliency. As another new sign at Wic̣aḣapi reads: "This sacred land continues beyond the boundaries of the park, spanning the bluffs along the rivers of this region, the Bdóte, and throughout Minnesota. Wóohoda. Please respect this place."

Our work at Wic̣aḣapi

Cultural memory and connection to this place makes stewardship of the land even more important. Since 2011, FMR has partnered with St. Paul Parks and Recreation to help restore and tend natural areas at the park.

At the time of initial European colonization, occasional natural and human-caused fires at the bluffs at Wic̣aḣapi would have helped dry prairie or oak savanna thrive. As St. Paul grew, development removed much of this habitat, and fire suppression and soil degradation damaged the park's remaining natural areas.

FMR and our volunteers have removed invasive plant species like buckthorn, burdock and garlic mustard and replaced them with native shrubs, grasses and wildflowers — a boon for wildlife habitat. We've also led forest management at the site, through removing invasive trees and thinning dead ash affected by emerald ash borer, all with the goal of transitioning forests toward woodland and savanna, the site's historical plant communities. We've also helped to return historical disturbance regimes through prescribed burns in the woodlands and prairies.

Restoring native prairie plants has helped reduce erosion, since their long, tough roots hold soft prairie soil in place. Without these plants, the bluff's soil can easily wash away in heavy rains.

Today, FMR is in a more supportive role at the site, with Wakáŋ Tipi Awaŋyaŋkapi and St. Paul Parks leading its stewardship. Ultimately, taking care of this place is a community effort. Public volunteers remove invasive species and plant native species that support pollinators and help stabilize the bluff around the park's main overlook. High school students have also stewarded the site and scientifically monitored both plant and insect diversity in the restored prairies.

Find out more and get involved

- Volunteer with us to restore places like this.

- Learn more about Dakota homelands.

- Check out the city's Cultural Landscape Study and Messaging Plan and updates.

- Visit Wakáŋ Tipi Awaŋyaŋkapi's webpage to learn more.

- Contact FMR project lead Leah Weston.

Partners and funders for our work at Wic̣aḣapi

This work is made possible by Saint Paul Parks and Recreation, the Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and by our generous volunteers and donors like you!

Where we work

FMR maintains over three dozen habitat restoration and land protection sites in the metro area.