Meet our Twin Cities locks and dams

The Mississippi River is the reason why Minneapolis and St. Paul were built where they are. People have lived in this area for thousands of years, drawn by the life-sustaining gifts of the river and the power of St. Anthony Falls, or Owámniyomni. Learn more about Dakota homelands. St. Anthony Falls is the only major waterfall on the entire Mississippi River, and as it moved over thousands of years, it carved the only gorge on the river, a beloved place for many residents.

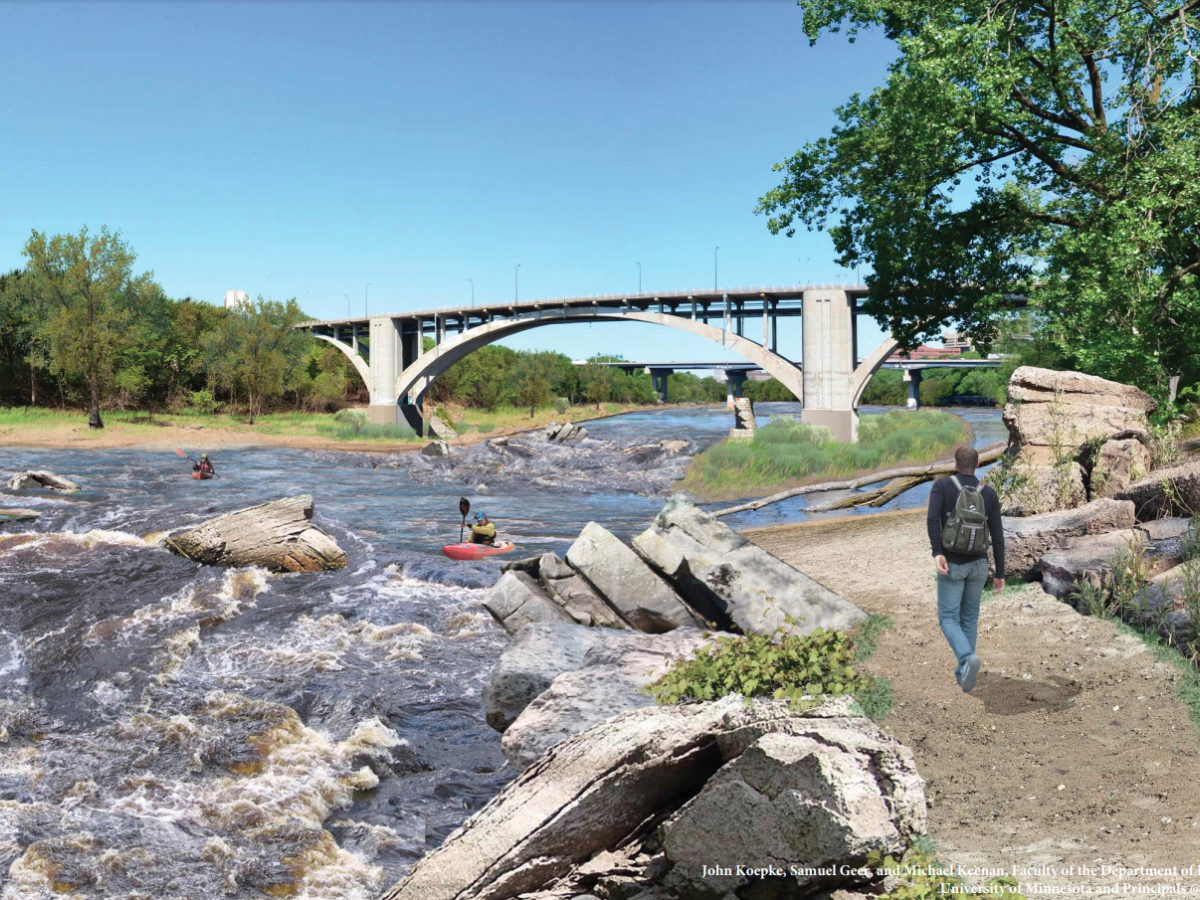

Though the river has always been dynamic, it looks very different than it did just a few centuries ago. In the past 175 years, people began making major engineering changes to the river in attempts to harness it for industry. Before we started building mills, dams and locks, the Mississippi here was a wild and free-flowing river.

Rather than the series of dammed reservoirs we have today, the river was a braided channel with at least a dozen islands between the falls and Bdóte, where the Minnesota River enters the Mississippi. The river had rocky rapids, gravel bars and beaches, fast and slow spots, deep and shallow spots and floodplains.

The river we see now is drastically different. And now we have a rare opportunity to consider whether we should restore this dammed section of the river to that freer, less-industrialized state by removing some of the locks and dams that have impounded it or leave it as-is.

Where are the locks and dams in the Twin Cities?

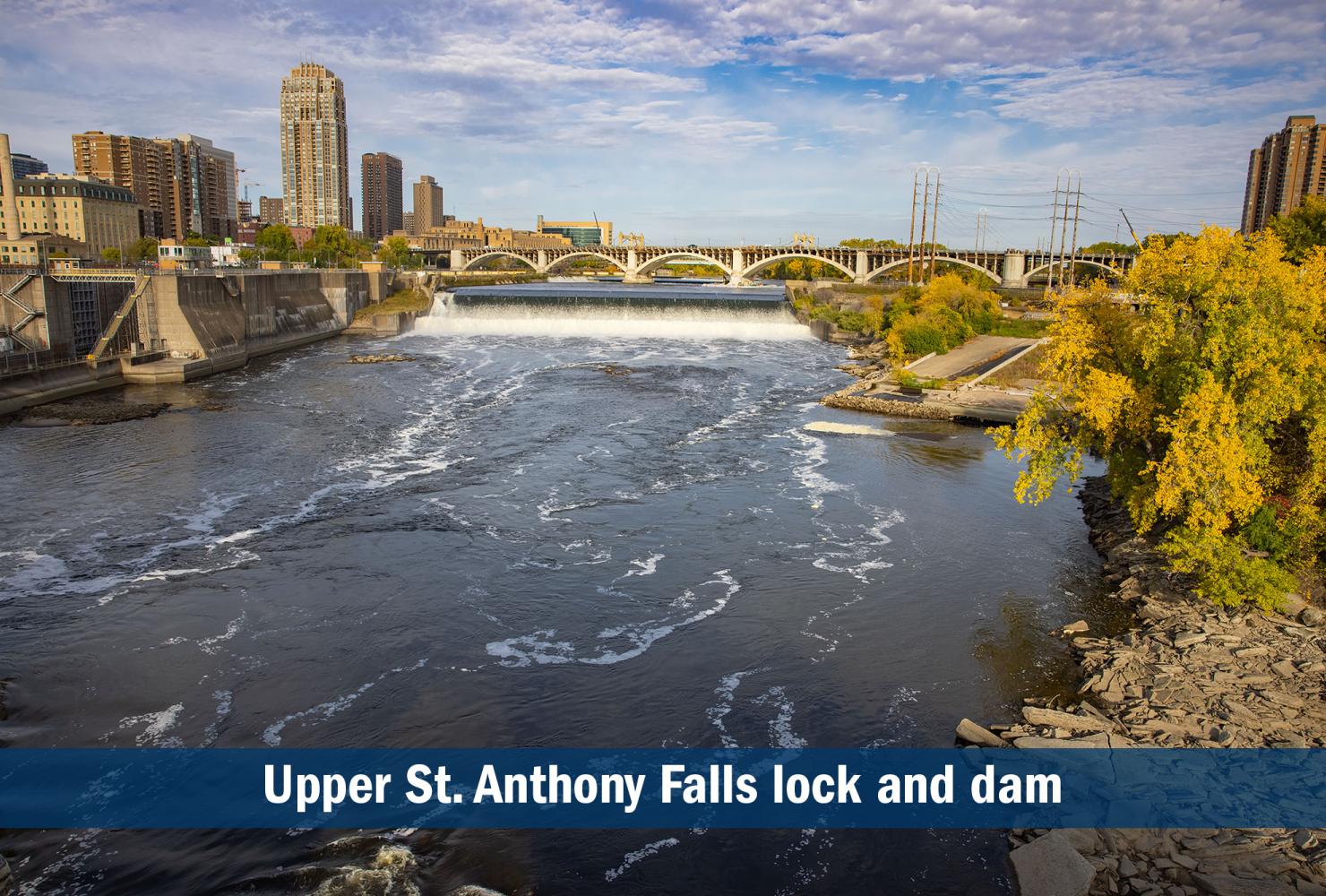

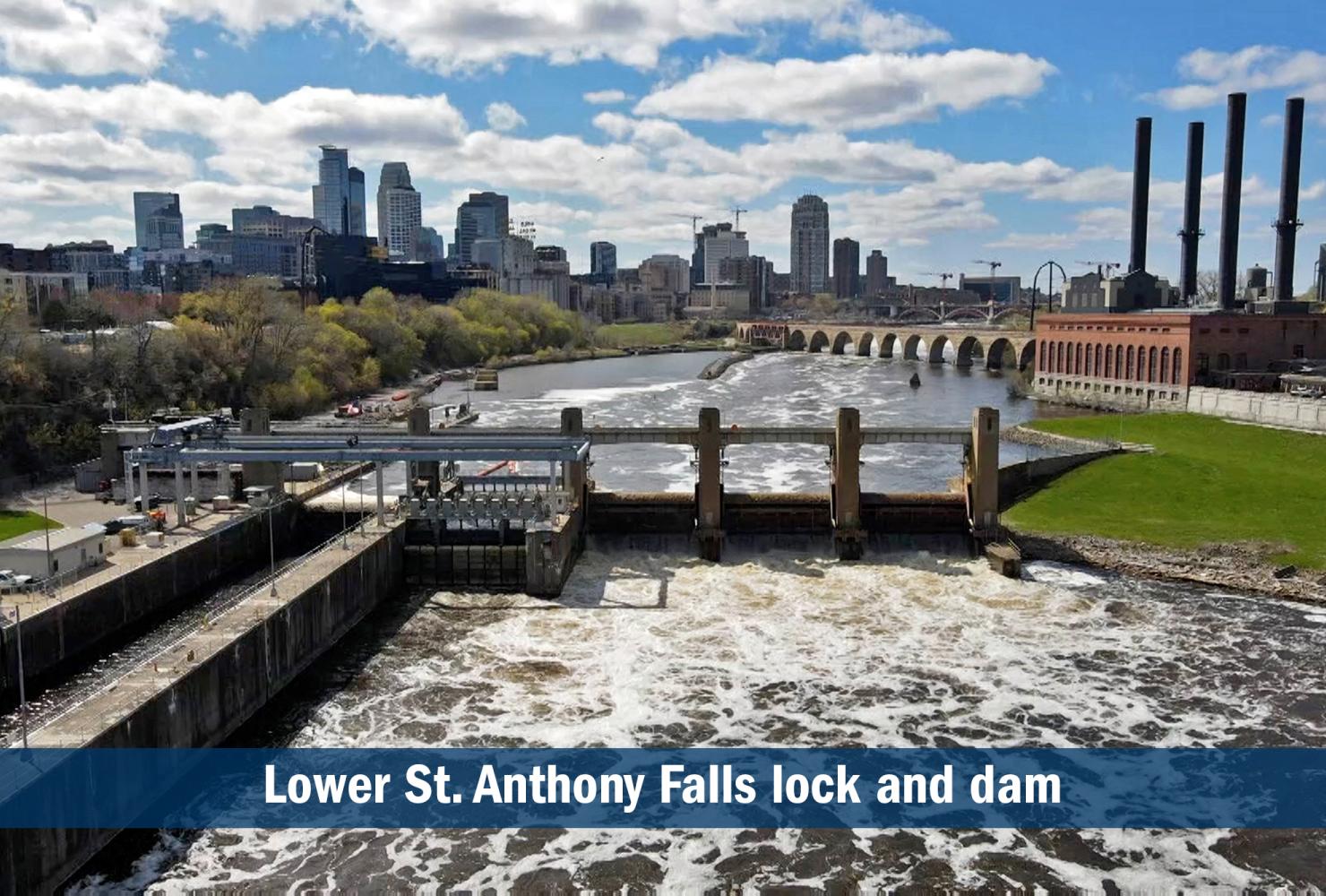

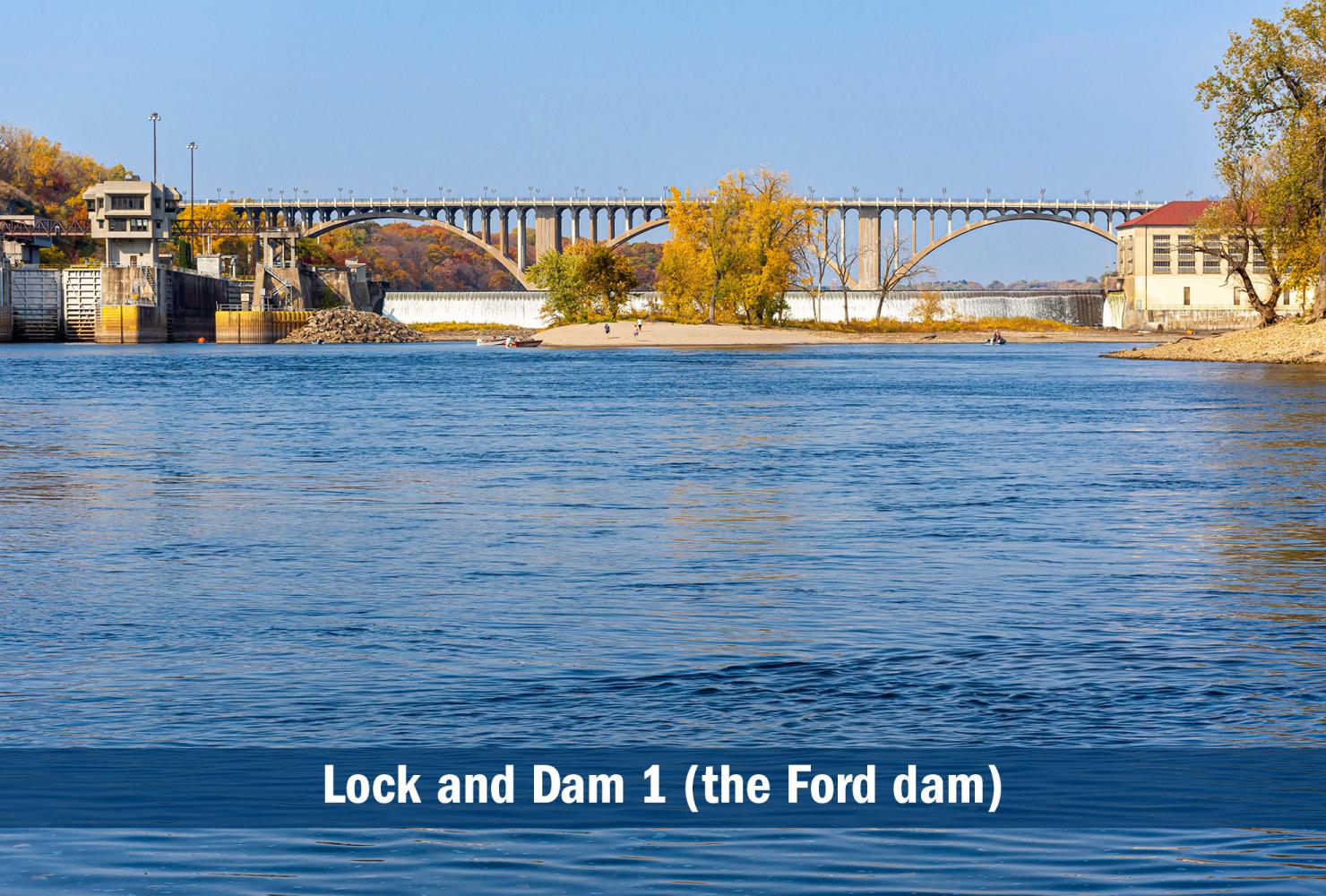

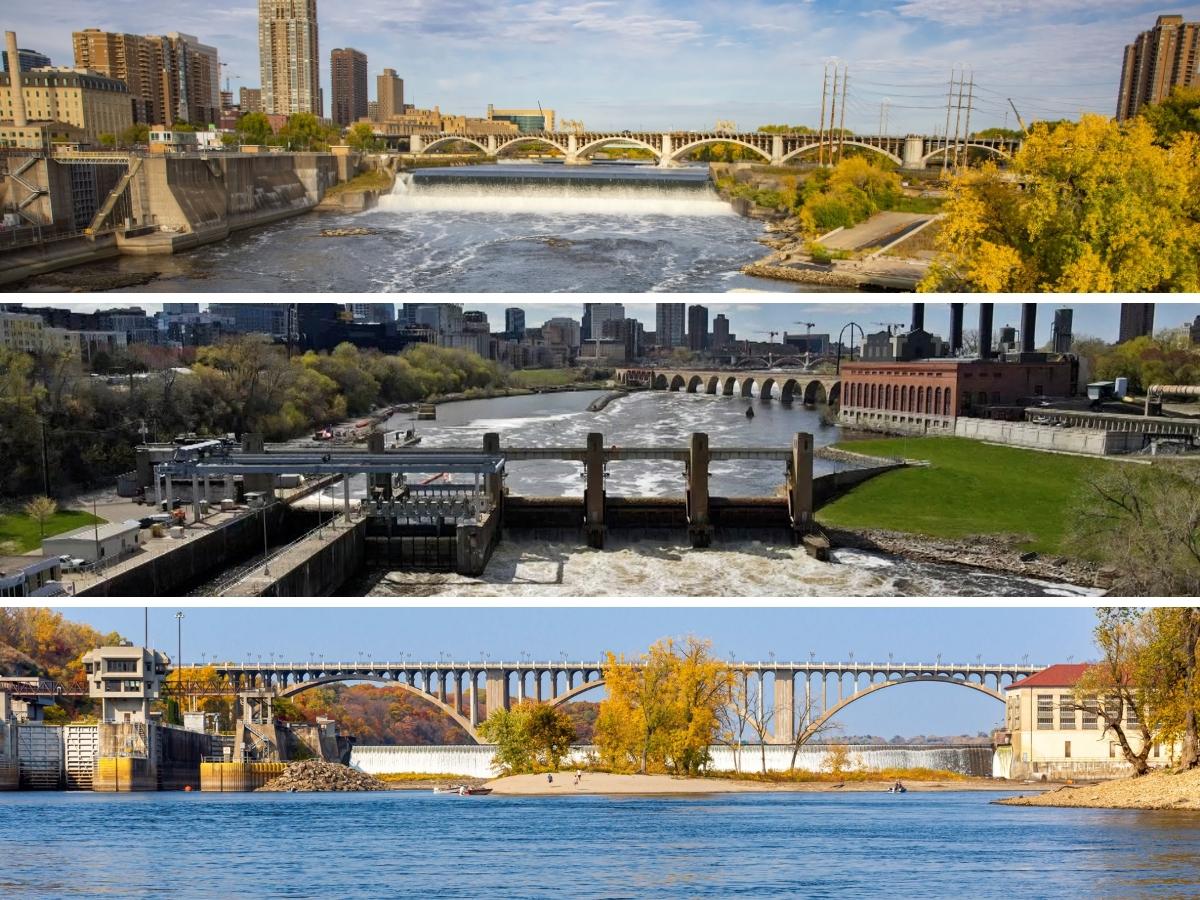

There are three locks and dams in Minneapolis and St. Paul: Upper St. Anthony Falls lock and dam, Lower St. Anthony Falls lock and dam and Lock and Dam 1 (the Ford dam).

Click the yellow dot and zoom in to see a photo of each Twin Cities lock and dam.

In downtown Minneapolis, the Upper and Lower St. Anthony Falls locks and dams are on either side of the Stone Arch Bridge. The concrete spillway and a wall under the Mississippi River at St. Anthony dam preserve what was a natural waterfall.

The Upper St. Anthony Falls lock and dam is the uppermost navigation dam on the Mississippi River. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers owns the lock, which has been closed to boat traffic since 2015 to reduce the spread of invasive carp (learn more about FMR's involvement). St. Anthony Falls flows over a concrete dam and spillway owned by Xcel Energy and used for hydropower production.

The Corps owns both the lock and dam at Lower St. Anthony Falls. Brookfield Energy leases the hydropower generation rights for the dam.

Roughly 5.5 miles farther downstream, the Ford lock and dam (known officially as Lock and Dam 1) spans Minneapolis and St. Paul near Minnehaha and Hidden Falls parks. The Corps also owns this lock and dam. Brookfield Energy leases the hydropower generation rights for the dam, which originally powered the nearby Ford Motor Company assembly plant.

Why were the locks and dams built?

People dam rivers for a variety of reasons. Dams create reservoirs for boating, water supply, hydroelectric power generation and help manage flooding. In our stretch of the Mississippi, the locks and dams were built primarily to facilitate barge shipping and enable hydroelectric power generation.

Before the dams were in place, steamboats struggled to navigate the Minneapolis-St. Paul stretch of the river because it was filled with boulders and rapids. Dams create wider, deeper, calmer pools or reservoirs of water that are easier for boats to navigate. At the end of each pool, the lock works like a water elevator to raise or lower a boat into the next pool.

A brief timeline of Twin Cities locks and dams

In 1917, the Corps finished Lock and Dam No. 1 and the base of a hydroelectric power plant. In 1923, Henry Ford saw the potential to build his vehicle assembly plant next to the river, giving the lock and dam the nickname the "Ford Dam," even though it was built before Ford came along. The Ford plant was powered by hydropower until it closed in 2011. Now owned by Brookfield, a Canadian energy company, the hydropower plant provides energy to the lock. The rest is sold back to the grid for use elsewhere.

To this point, major shipping activity was limited to St. Paul and downstream. But for Minneapolis to compete with St. Paul as a port city, barges had to get above St. Anthony Falls. The gorge below the falls is too narrow, and the bluffs too steep for a substantial barge terminal.

The city, therefore, lobbied Congress to build two more locks near the Stone Arch Bridge to help barges get up over St. Anthony Falls to areas with flatter shorelines more suitable for industry. Lower St. Anthony Falls Lock and Dam opened in 1956, and Upper St. Anthony Falls lock opened in 1963. The dam had already been built many times over by millers and other private owners.

In 1968, Minneapolis began building a barge terminal, Upper Harbor Terminal, in North Minneapolis. Several private companies in North and Northeast Minneapolis had barge docks as well. But Minneapolis' river shipping never really lived up to initial projections and was fading away when Congress closed the Upper St. Anthony Falls lock to boats in 2015.

That year, all three of these locks stopped serving commercial barge traffic. Since that was the primary purpose for building locks in the first place, we have an opportunity to consider whether we still need and want these structures.

It's important to remember that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built these locks and dams. They are owned, operated and maintained by us as public taxpayers. They were built because the community here advocated for them to be built. We can tap into that same community power to advocate for whatever we decide the future of these structures should be.

Learn more and get involved

This process will unfold over many years, and FMR will be involved every step of the way.

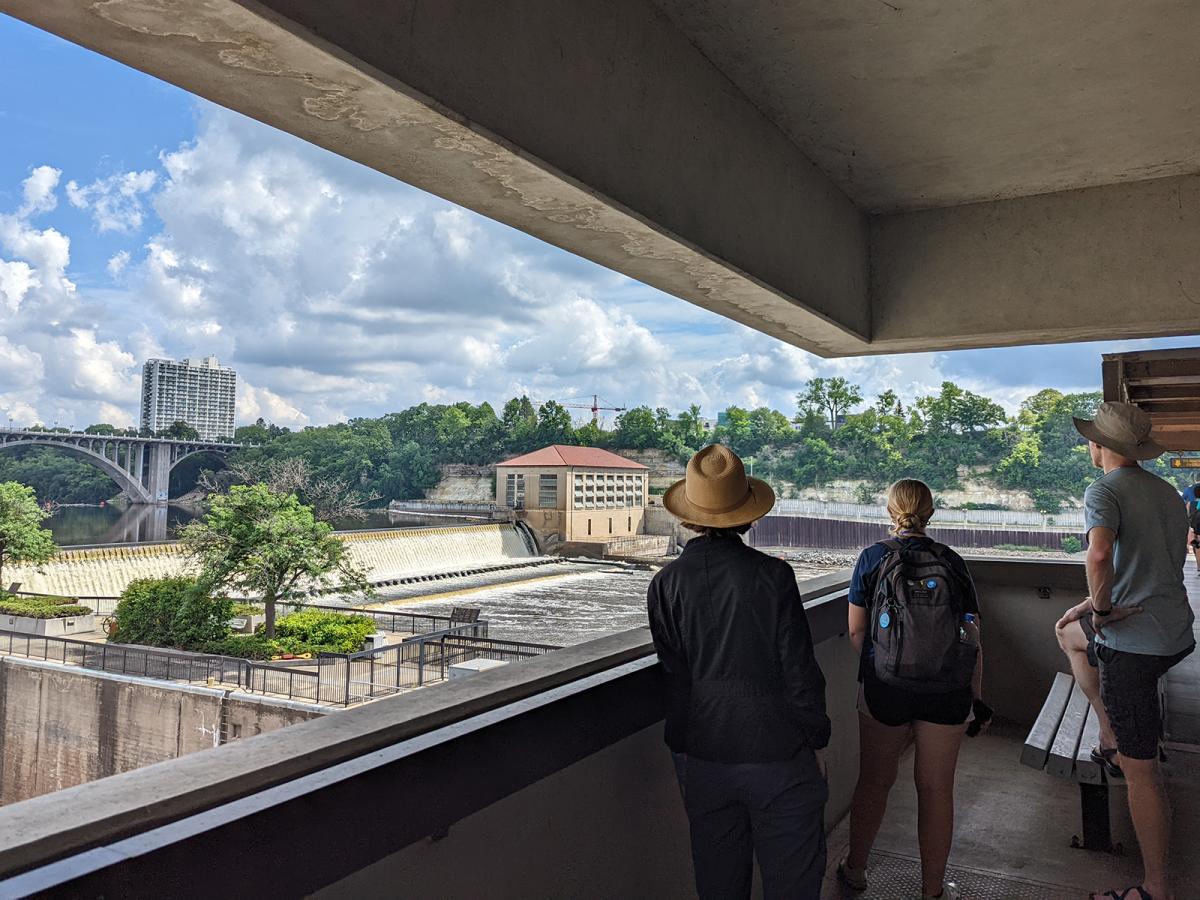

We'll host a variety of workshops, tours and events about the future of Twin Cities locks and dams in the coming years. We're also happy to give special presentations to community groups upon request. And we'll be sure to tell our advocates about ways to weigh in and shape the future of our metro river.

Learn about Twin Cities locks and dams, the pros and cons of removal and more here. For additional details, contact FMR Land Use & Planning Program Director Colleen O'Connor Toberman, ctoberman@fmr.org, 651.477.0923. The best way to keep up with the latest news and hear about opportunities to get involved is to sign up as an FMR River Guardian below.

Become a River Guardian

Sign up and we'll email you when important river issues arise. We make it quick and easy to contact decision-makers. River Guardians are also invited to special social hours and other events about legislative and metro river corridor issues.

Removing two metro locks and dams would reconnect 39 miles of river through the Mississippi's only gorge, which is located right here in the heart of the Twin Cities. But is dam removal the best scenario for our metro river? Here's what we need to consider.

What will happen to metro locks and dams? Here's a rundown of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers disposition study process and timeline, the scenarios under consideration, plus ways you can shape the river's future.

To keep up with the latest developments around this process and hear about how you can weigh in, check out our most recent articles on locks and dams.