What tiny aquatic insects can reveal about water quality

Alexandra Jabbarpour is FMR's lead for the Stream Health Evaluation Program and the artist behind these aquatic macroinvertebrate illustrations.

Every year since 2006, FMR volunteers have waded into creeks, collected samples of small insects, crustaceans and other critters, and identified them via microscopes. Why? Monitoring these aquatic macroinvertebrates can offer insights into water quality.

Living water quality indicators

FMR's Stream Health Evaluation Program (SHEP) in the Rice Creek Watershed District trains volunteers to sample and identify benthic macroinvertebrates — small aquatic animals and insects in aquatic larval stages.

Aquatic macroinvertebrates are essential to our freshwater ecosystems. But some are more tolerant of pollution than others. Pollution-tolerant families of macroinvertebrates can survive in both high and lower quality water. But pollution-sensitive families can only survive in higher-quality water. If SHEP volunteers find a high number of families that are pollution-sensitive at a site, that could point to stream health, as could a higher diversity of macroinvertebrate families overall.

To make sense of our volunteers' findings, we calculate a score based partly on the average pollution tolerance of all families identified in a sample. This score, the Family Biotic Index, gives us a fuller picture and becomes a valuable indicator of overall stream health each year.

Here's a glimpse into what kinds of animals SHEP volunteers sample and what the presence of each could mean about the stream where it lives.

Three creek critters and what they might signal about water quality

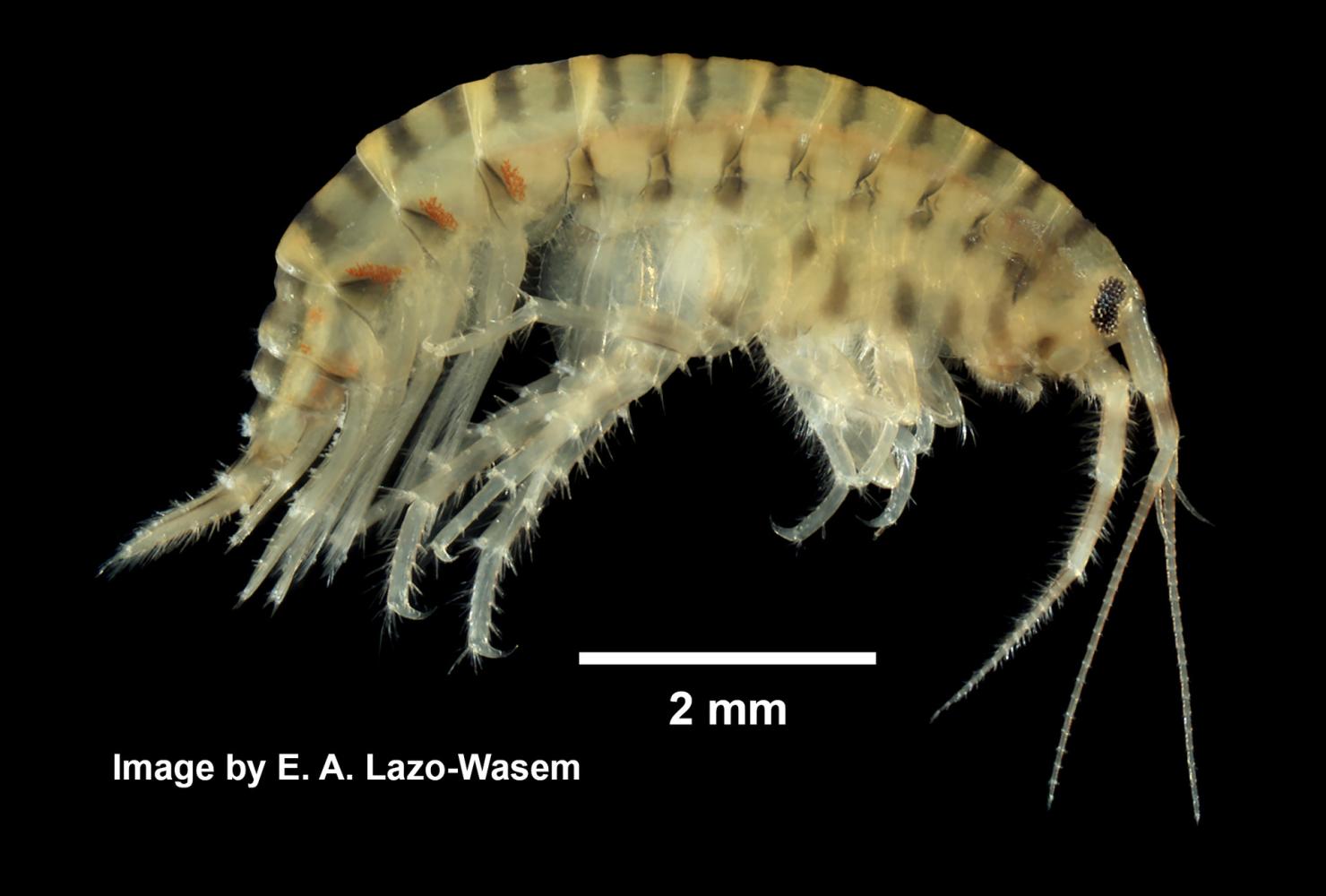

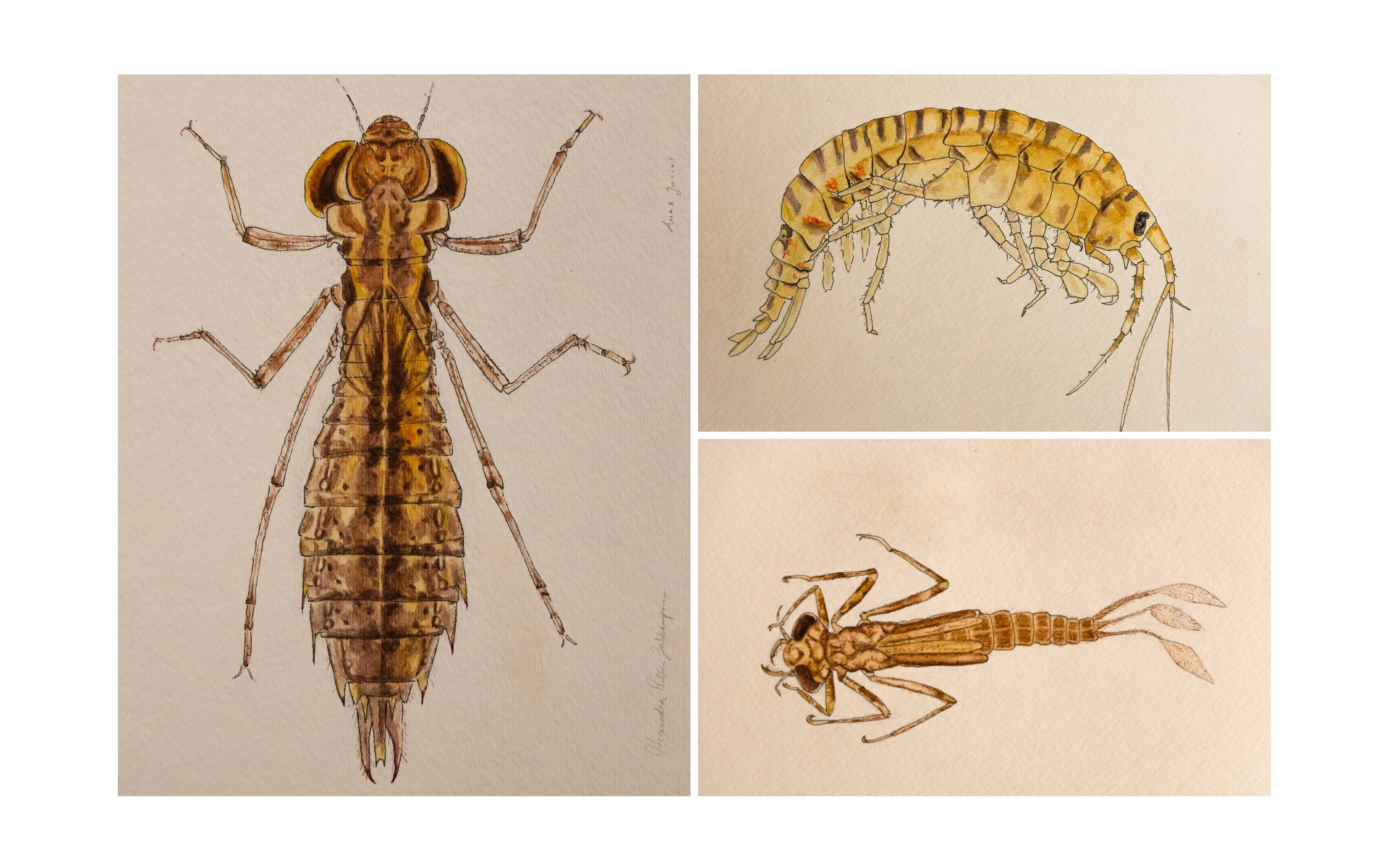

Scuds (Gammaridae family)

Illustrated example: Gammarus fasciatus

Pollution tolerance value: 4 (on a scale of 0-10, where 0 is low tolerance)

Gammaridae are in the same category as shrimp, crabs and lobsters. These creatures are small (5-20 millimeters), between the size of a pencil top eraser and a shelled peanut. Scuds can be an important food source for fish and other invertebrate predators. In water bodies without fish, they can be extremely abundant. They play a central role in breaking down organic matter and generally live in shallow regions. SHEP volunteers often find them in snags and vegetation.

What we've found

SHEP data shows a lot of variation in Gammaridae abundance from year to year. Scuds have been the most common family sampled some years, but not found at all in other years. That's why it's helpful to look at a stream's overall Family Biotic Index, and not just one sampled family, over time.

In one stretch of Hardwood Creek in 2024, volunteers identified 281 invertebrates, and 92.5% of those were in the Gammaridae family. Finding so many specimens from a family with a moderate pollution tolerance value might seem like generally good news about stream health. But the sample was dominated by just this one family. That lack of diversity can indicate a degraded water body.

Darner dragonflies (Aeshnidae family)

Illustrated example: Green darner dragonfly larva (Anax junius)

Pollution tolerance value: 3 (on a scale of 0-10, where 0 is low tolerance)

Darner dragonflies stalk their prey and are important predators. In their larval form they eat other invertebrates and even small fish. Since they're higher on the food chain, toxins such as heavy metals bioaccumulate in darner dragonflies faster than in some other macroinvertebrates.

Darner dragonflies are among the more pollution-sensitive families, which means they likely won’t be able to survive in water bodies that have higher levels of pollution. When volunteers come across one of these in their samples, it's exciting both because it may be a sign of higher water quality and improving steam health — and because of its striking size. The larvae are about the size of one to two paper clips (30-62 millimeters).

What we've found

SHEP teams have documented darner dragonfy larvae in creeks, including in 2022 and 2023. But in 2024 we only identified it in one of the nine streams that SHEP samples. In this stream, we found two larvae for the first time since 2010. Depending on the rest of the sample, finding a darner dragonfly can be a good signal about stream health.

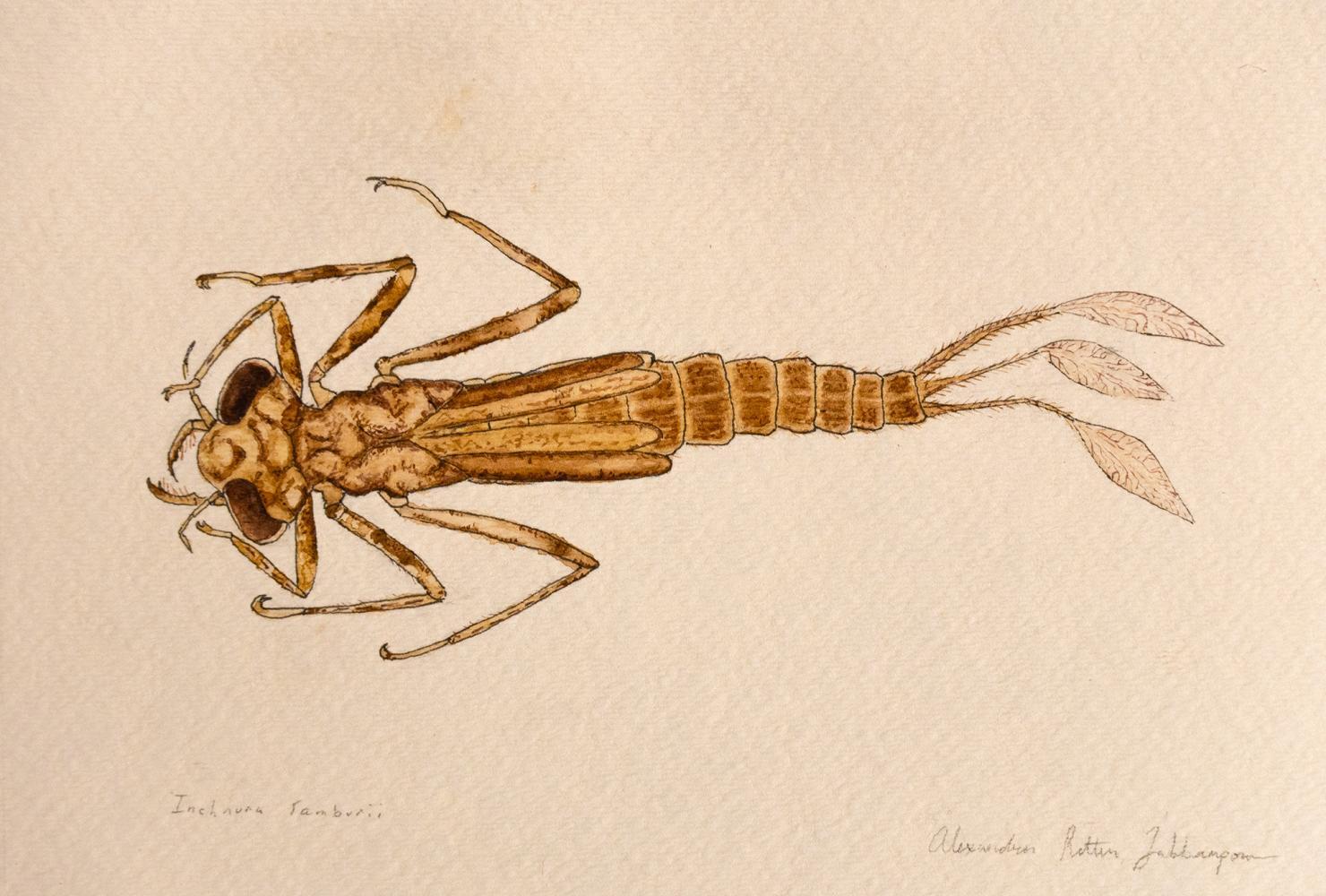

Narrow-winged damselflies (Coenagrionidae family)

Illustrated example: Rambur's forktail damselfly larva (Ischnura ramburii)

Pollution tolerance value: 9 (on a scale of 0-10, where 0 is low tolerance)

The length of these damselflies is about half a paperclip to a paperclip long (15-30 millimeters), and we find them in a variety of habitats, from ponds and wetlands to moving water. Although many damselflies are very pollution-sensitive, biology loves breaking rules. Narrow-winged damselflies actually have a relatively high tolerance to pollution.

What we've found

Sampling pollution-tolerant critters doesn't signal lower water quality on its own. Narrow-winged damselflies can thrive in a variety of conditions, including polluted and non-polluted water bodies. However, if we only see highly tolerant families, especially very few of them, the lack of diversity and lack of other lower-tolerant families show the fuller picture of a potentially polluted water body.

For example in 2024, we found 17 narrow-winged damselflies in one creek, making them the second most dominant family of 14 different families in that sample. The sample also included a few highly sensitive families. But the creek's overall score landed the stream in the category of fairly poor, with substantial pollution likely. That's an outcome that's possible, but not always expected, given the tolerance value of these narrow-winged damselflies.

Learn more about the Stream Health Evaluation Program and its findings

You can read more detailed findings in our annual SHEP reports. Each year, we submit this report to our partners and funders at the Rice Creek Watershed District. SHEP's growing data set is a valuable reference for city workers and researchers to see what changes in water quality may be due to environmental shifts or human-imposed developments.

Get involved

Our volunteer SHEP teams sometimes have openings. Preference is given to Rice Creek Watershed District residents, who are especially encouraged to apply. (Check this map to see if you live in the watershed.) You can learn more about volunteering here and contact SHEP@fmr.org if you want to sign up.

Project support

SHEP is made possible through funding and support from the Rice Creek Watershed District, our SHEP volunteers and team leads, as well as our longstanding partnership with field biologist, Katie Farber of Bolton & Menk, Inc.

Some of the above information came from the Guide to Aquatic Invertebrates of the Upper Midwest, created by R.W. Bouchard, Jr. through the Water Resources Center at the University of Minnesota.