Lessons from the Dust Bowl: A cleaner Mississippi is rooted in a new farming paradigm

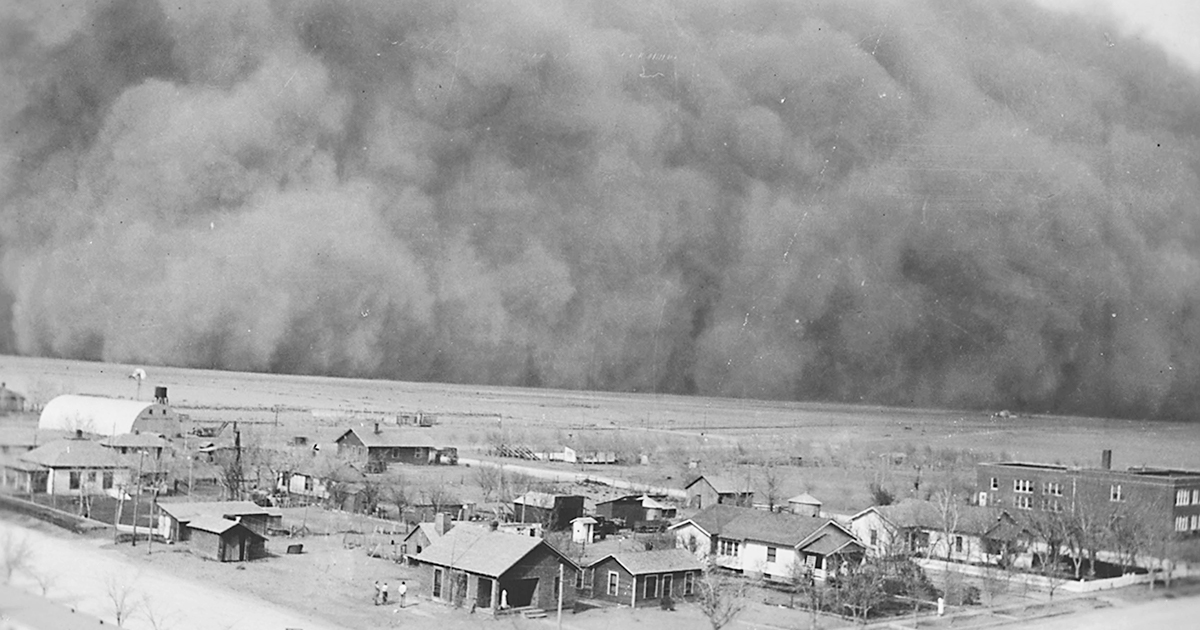

Our agricultural practices caused disastrous dust storms like this one in Kansas in 1935. Generations later, the way we farm has again led to grave challenges — unsafe drinking water and the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico. What can the Dust Bowl teach us about how to move forward? (Photo: Public domain)

You’ve seen it in old photos and films: the colossal dust cloud boiling out of the land, bringing chaos and then an eerie quiet.

My grandparents were teenagers when storms scoured the Great Plains and dumped its topsoil as far away as the Atlantic, when desperation drove tens of thousands of Americans out of the country’s middle states, when migrants’ dreams of making a living on the land turned into the nightmare of the Dust Bowl.

It was a “natural” disaster only in the loosest sense of the term. The prairie had been resilient to drought and gales for millennia until “sod-busting” settlers, egged on by a booming grain market, uprooted earth's protective skin with the moldboard plow. Nothing was left to break the wind or hold the ground down.

Farmers and scientists responded to the crisis by learning how to work with the land, replanting trees and sharing new agricultural methods through a network of Soil and Water Conservation Districts.

The way we farm now has brought on a new set of crises just as devastating as the Dust Bowl: a dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico, increasingly polluted drinking wells and surface water, and a river that doesn't fully support aquatic life. As Mark Twain is thought to have said, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” Three generations later, it’s time for another farming paradigm shift.

Our Dust Bowl: The dead zone and undrinkable water

It's clear at the confluence: The Mississippi River (right) takes in all the sediment and runoff pollution that the Minnesota River (left) picks up as it runs through agricultural land. By the time the Mississippi makes it to the Gulf, the Big Muddy holds enough fertilizer and sediment pollution to cause the disastrous dead zone. (Photo: Tom Reiter for FMR)

If you drive across rural Minnesota during the summer, you’ll pass mile upon mile of soybeans and corn stalks. These two plants have come to dominate our landscape relatively recently. Federal policies, industrial markets and technological advances have put a major thumb on the scale and incentivized such “row crops” — chiefly for ethanol and livestock feed — over diverse crops.

Despite the lessons of the Dust Bowl, typical Minnesota row cropping practices expose the earth to the elements for over half of the year and degrade the health of the land.

Farmers, facing thin profit margins, utilize nitrogen and other fertilizers to boost the depleted soil. When rain falls or snow melts, excess nutrients wash off fields into drainage ditches and streams, or even seep into wells. Today, an increasing number of Minnesotans struggle with water supplies contaminated by nitrate levels that exceed federal drinking water standards.

The Mississippi River basin funnels rain and snowmelt from 40% of the continental U.S. into the Gulf of Mexico. Each summer, nutrient runoff from the Heartland’s farms catalyzes a phenomenon known as a “dead zone,” where excess nutrients trigger the explosive growth and death of trillions of suffocating algae and phytoplankton.

The Mississippi River Delta as seen from space this April shows sediment washed downstream and into the water along the coastline. Flooding and increased polluted runoff led to another costly dead zone. (Photo: Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, NASA Johnson Space Center)

Like a marine wildfire, these tiny organisms suck all the oxygen out of the water and block sunlight, wiping out fish, ocean plants, crustaceans and the coastal economies that rely on them: The ruin caused by this summer’s 7,000 square mile dead zone forced Gulf officials to ask the White House to declare a fisheries emergency. How can we fix a breakdown of this scale?

Starting at the roots

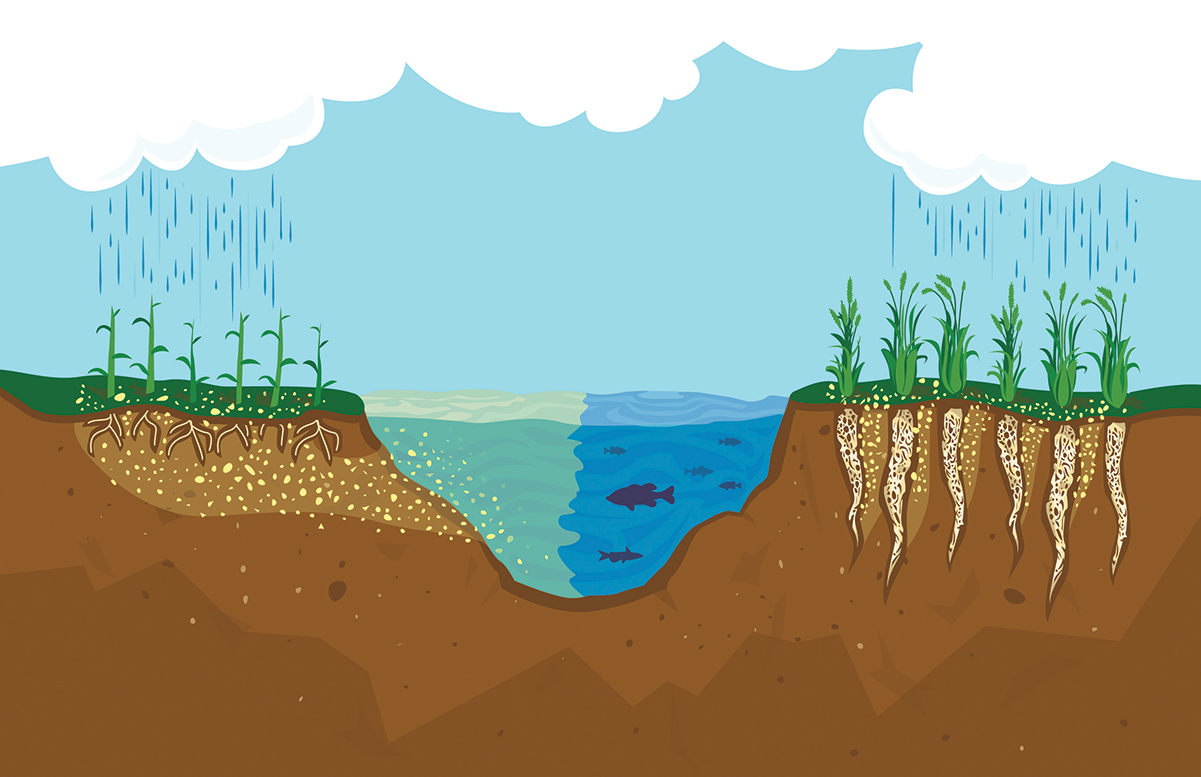

The Great Plains blew away in the 1930s because we pulverized the prairie’s living root system, and most of today’s row crop operations (which is to say, most U.S. agricultural crop production) still discount living roots and apply nutrients with an eye on yields rather than health or environmental impacts.

A healthier system centers crops that mimic the functions of native prairie, creating “continuous living cover” on the land. These cropping systems require considerably less fertilizer and build climate resilience. But changing systems is risky, and farmers, already challenged by extreme weather and global economic headwinds, can’t go it alone.

This is why FMR is working with partners across the spectrum — from farmers and agribusiness to academic researchers, environmental groups and government agencies — to develop markets, advance policy solutions and ultimately secure widespread adoption of these new cropping systems.

Forward-thinking farmers are already implementing “no-till” and “strip-till” practices that leave a crop’s root mass and surface cover intact after harvest.

They’re also expanding the window of living greenery by planting cover crops — species that grow quickly in early springtime before the cash crop is sown or after its harvest. These cover crops also offer habitat for pollinators, build topsoil and decrease the need for fertilizers and herbicides.

New varieties of annual oilseeds like pennycress and camelina could provide farmers an additional cash crop profit with cover crop benefits. And perhaps most intriguingly, agronomists are breeding market-ready perennial plants that don’t die after harvest, such as perennial sunflower, silphium and a wheat-like grain called Kernza®, whose dense root systems act as a year-round living filter.

Perennial crops (right) are good for water for the same reasons prairies are: year-round deep roots. They hold soil in place, reducing erosion. And they don't leak crucial nutrients, like nitrates, as much as conventional crops (left). (Illustration: Kimberly Boustead and Emily Sauer)

Giving ground to hope

None of this comes easily. Improving tillage practices and sowing cover crops can be pricey. Kernza® and other next-generation crops are still several years away from commercial-scale production.

These are real hurdles, but we’re at a unique moment in history when technology, insight and consumer demand are aligning to create a path forward. FMR’s job is to support a growing network focused on making steady progress down this path. Through our combined energy, Minnesota could emerge as living proof that change is possible.

In 1933, at the worst point of the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression, President Coolidge lamented, “I now see nothing to give ground to hope — nothing of man.”

It took the united strength of a nationwide effort and wholesale shifts in agricultural practices, but hope prevailed. FMR is committed to another shift, this time toward continuous living cover and a sustainable future for the Mississippi River and all that depend on it.

Join us!

Sign up as a River Guardian and we'll email you when there's a chance to act quickly online for the river. Plus, you'll be invited to special events like educational happy hours.

To stay up to date on the transition to clean-water agriculture, follow our water blog.