Explainer: How jet fuel from crops can help (or hurt) water quality

Anything big we do in the transportation and biofuels space needs to account for how those changes to agricultural practices will impact water quality — both positively and negatively. (Photo by David Kosling, USDA)

In recent decades, U.S. transportation emissions reductions have focused on biofuels — fuel made from crops (such as corn or soybeans) or other biomass (like algae or woody debris). As a result, biofuel policies targeting the transportation sector have also become some of the nation's most influential agricultural policies.

That has great consequences for the Mississippi River.

Because agriculture is a leading source of pollution to our state’s waters, transportation policies that incentivize certain farm practices over others can have a significant effect on our great river.

And right now, the river and its watershed — though healthier than they've been in decades — are struggling.

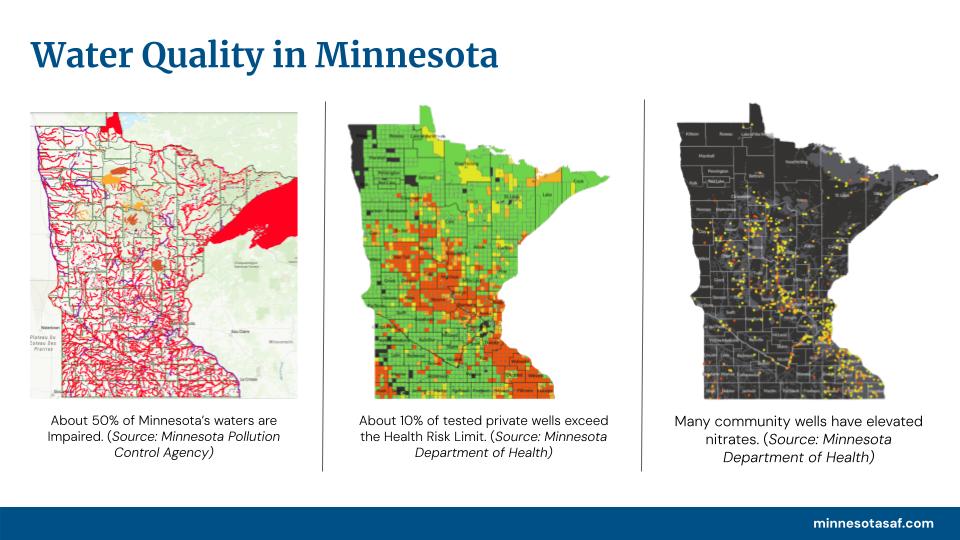

Data from state agencies demonstrate the scope of the water quality challenge in Minnesota. This image was taken from the webinar "How Minnesota can get sustainable aviation fuel right."

About 50% of Minnesota’s waters don’t meet water quality standards, according to Minnesota Pollution Control Agency data. That includes every mile of the Mississippi River in the state (see left).

Groundwater is also at risk. Minnesota Department of Health data show about 10% of private wells tested in the state fail to meet drinking water standards for nitrate. Several hundred communities have elevated levels of nitrate in their community wells.

The U.S. EPA even intervened to force more state action on nitrate in the eight southeast Minnesota counties that are at increased risk due to Karst topography.

Anything big we do in the transportation and biofuels space needs to account for how those changes to agricultural practices will impact water quality — both positively and negatively.

This is true for sustainable aviation fuels — also called "SAF" — as much as anything else.

An approach to SAF that relies on the current dominant cropping systems (such as corn and soybeans) might reduce aviation emissions in a vacuum. But it would very likely have unintended consequences for agriculture and water quality.

Producing enough SAF with these row crops to meet the the aviation industry's needs would require a large increase in production (meaning significantly more acres). This could result in increased fertilizer and herbicide pollution, worsening soil health, more pressure to convert conservation lands into cropland, and a reduction in diverse crop rotations.

All of this would mean fewer choices for farmers and more pollution to our waters.

There is a scenario where we might see modest improvements, or at least limited negative consequences. A row crop-based SAF — if kept to the same acreage that currently exists — might bring about small improvements to water quality by incentivizing or requiring producers to adopt certain conversation (e.g. cover crops, no-till, optimum nutrient management) in order for those crops to quality as SAF.

However, there is a purpose-grown crop option that we’re most excited about, because it would be truly transformative: winter oilseeds.

Oilseeds: The best tool in the toolbox

From a water quality and soil health perspective, the biggest problem with most row-crop systems is that they only have living plants in the ground for a few months in summertime. This leaves the ground unprotected the rest of the year. One particularly effective solution is to use cover crops, which get planted after the fall harvest, go dormant overwinter, and emerge early in the springtime to help mitigate early-season rain events and create biomass.

Common cover crops like winter rye improve yields and resilience in the long-term, but Minnesota has a cover crop adoption rate of about 2-4%. Why? Well, these cover crops cost money and hassle in the near term, and there isn't much of a market for them in the long-term. Farmers can't harvest and sell these crops for much money — if any at all.

Winter oilseeds are different. These are just what they sound like: crops that produce seeds with a high oil component, and that are able to survive our harsh winters.

Forever Green at the University of Minnesota'e is developing two of these crops, winter camelina and field pennycress. Both can be used for a variety of products, including SAF.

Winter oilseeds have ultra-low carbon intensity scores, much better than soybeans or corn and up to 70% lower than conventional jet fuel. They also bring significant benefits for soil health, create habitat for pollinators and other wildlife, and greatly reduce both erosion and nutrient loss.

Perhaps most importantly, these crops help farmers make more money.

Because of the emerging SAF market, winter oilseeds have an immediate payoff. And because they fit into rotations with those dominant summer crops, they unlock significant additional income streams for farmers without requiring more farmland. This means that they have a real chance to achieve scale — millions of acres in Minnesota alone that could fuel our planes and protect our waters.

News outlets from across the state reported on the first commercial flight using a winter camelina blend SAF in September 2024. This image was taken from the webinar "How Minnesota can get sustainable aviation fuel right."

This isn’t pie-in-the-sky thinking, either. It’s real, it works and it’s safe.

In September of 2024, the Minnesota SAF Hub coordinated its first flight fueled with a winter camelina blend. Major companies are investing millions into research partnerships and farmer adoption because they see the tremendous promise of these feedstocks. And a recent analysis projected that, with proper investments, we could have up to 9 million acres of winter oilseeds in Minnesota alone by 2050.

For all of those reasons, we’ve made winter oilseeds a central component of the SAF Guiding Principles.

There are additional long-term SAF pathways we should be building toward. But with climate change upon us, we need to act now and explore every tool in the toolbox to mitigate its impact.

Winter oilseeds are the right tool for the moment. They’re not just a super low-carbon aviation fuel — they’ll greatly contribute to clean water and prosperous farms.