Climate change, climate justice and FMR's Land Conservation program

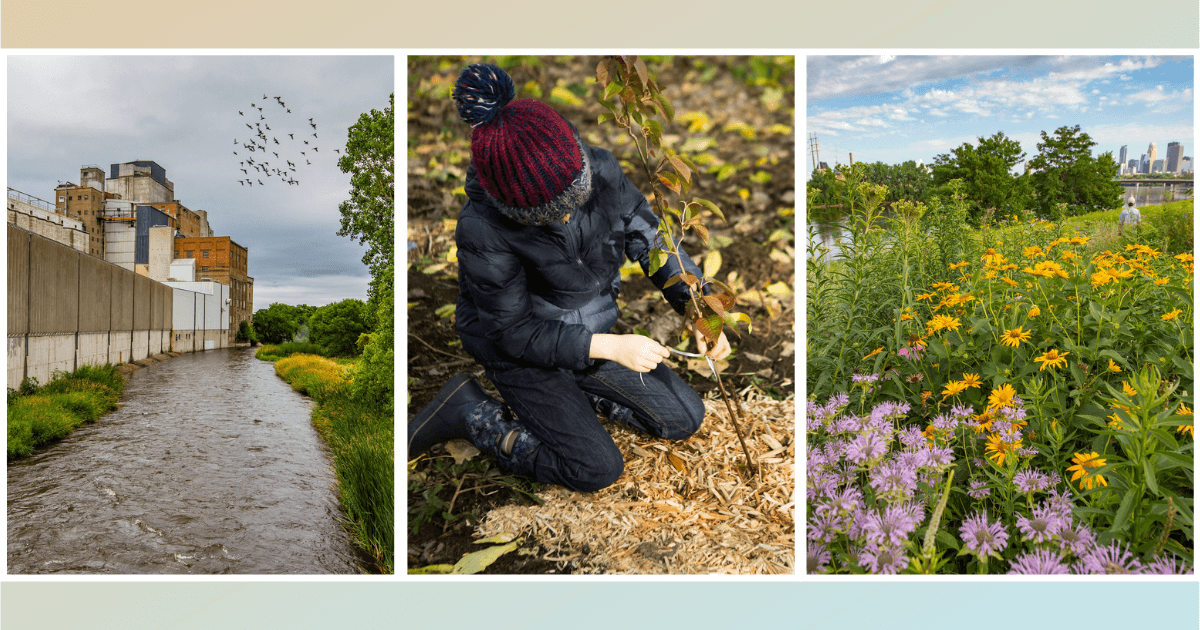

Land protection and restoration for ecological diversity keep our urban environments cooler and more resilient in the face of climate change. (Image credits, left to right: Tom Reiter for FMR, Will Stock for FMR, Tom Reiter for FMR)

At FMR, we're proud of our land protection and restoration history in the Twin Cities metro. While we've accomplished a lot, Minnesota's uncertain climate future makes it all the more important that we advance our mission of protecting and restoring land for habitat, water quality and recreation.

Climate change threatens the health of Minnesota's natural areas in a number of ways. Minnesota is likely to see more severe storms, significant rain events and even droughts. Increasing temperatures may mean certain Minnesota species find our landscape less hospitable. And changing conditions will bring new and challenging issues, including new invasive species and diseases.

As with many issues, the effects of climate change are predicted to disproportionately affect BIPOC populations. While we haven't traditionally centered our conservation efforts around BIPOC communities, it's important to continue to explore how our Land Conservation program intersects with climate change and climate justice to make sure our work is as equitable as it can be.

Conservation is key

To combat the effects of climate change, Minnesota needs healthy, diverse natural ecosystems. These systems are better able to withstand disturbance events, like flooding along our rivers.

In part, that's why much of our restoration takes place along the Mississippi River and its tributaries, since that's where we can alleviate flooding and its impacts. Sometimes this means replacing turfgrass with native vegetation — as we did at Orvin "Ole" Olson Park in North Minneapolis — or restoring floodplain forests with diverse, deep-rooted native species as we have at Gores Pool Wildlife Management Area. At other sites we may take on specific projects aimed at protecting a site from erosion caused by flooding, as we have at Vermillion River Linear Park in Hastings.

Many of these projects are located in public natural areas. Of course, these projects can have a more tangible climate justice connection when they're in historically or presently BIPOC-majority neighborhoods in the metro, like Ole Olson in North Minneapolis.

However, most undeveloped natural lands are found in rural areas, making it all the more important that we work to protect what public land we can in the city. This work intersects with our River Corridor program's access and equity work in North Minneapolis and St. Paul where we're striving to protect parkland for habitat, water quality and access.

Cooling corridors

As temperatures rise, natural areas become important for both local cooling and the potential they hold for plants and animals to migrate to more hospitable places.

The urban heat island effect is a well-known phenomenon, and warming temperatures will exacerbate this effect. With a disproportionate number of BIPOC residents living in urban areas, natural habitat in the urban landscape is vital for providing respite from the heat.

At all of our forest restoration sites, one of the main steps in restoring these systems is engaging volunteers to plant native trees and shrubs once invasive plants are removed. These volunteer events not only expose people to the natural spaces in their own neighborhoods, but they also help the site recover and provide habitat for local wildlife.

We're also planting the future canopy in these areas, helping to pull carbon out of the atmosphere and to increase shading and natural cooling. Especially in the Twin Cities, most of the trees we're planting are climate-adapted species, or those predicted to do well in our predicted future climate.

Prairie vegetation is also important for reducing urban heat, as prairies stay up to 5 degrees cooler than surrounding concrete surfaces. Even small prairies can provide habitat for pollinators, aesthetic beauty, and this cooling effect, including the restored prairie at Ole Olson in North Minneapolis. All of this helps to both combat climate change and make strides toward climate justice.

When we string natural areas together, we build valuable corridors along rivers, streams and other bodies of water. These corridors become pathways for migrating animals, including many species stressed by climate change.

Corridors that include or are surrounded by native habitat not only improve the migration potential of the area, but also protect water quality and public access. It's well-known that experiencing nature provides a respite and stress release for people. In addition to reducing climate change impacts, FMR's restoration work in urban areas helps create connections to nature in communities historically excluded from access.

The power of diversity

Lastly, climate change will present many new challenges to natural areas and habitat management, including new invasive species, pests and diseases.

Many of these issues can severely degrade our natural systems, decreasing their value for habitat, water quality and recreation. For example, buckthorn can form impenetrable thickets in woodlands and forests. It not only outcompetes native plant species and changes usage patterns by wildlife, but prevents recreation and decreases safety.

When damaging species like buckthorn take over woodlands, as they have throughout most of the metro area, they form impenetrable thickets. Such areas can be foreboding and unwelcoming, especially for BIPOC and other people who have safety concerns in secluded places.

Species like buckthorn also push out native plant species. With fewer native grasses and wildflowers growing and regenerating, invasive plants increase erosion and decrease carbon storage, which harms water quality and exacerbates climate change. And once invasive plants crowd out native plants that pollinators, birds and other animals depend upon, wildlife is forced to find sustenance and habitat elsewhere.

So while they may look green, parkland spaces full of invasive plants can become, in effect, deserts lacking native plant and animal diversity and sitting unused by people.

When we restore a site's ecological diversity, we improve its habitat and water quality value while also making it more inviting to people. Ecological diversity is one of the key drivers behind resiliency, or a system's ability to resist and recover from disturbances. Increasing diversity can help make sites more resilient to warming temperatures and other future threats. FMR's Land Conservation program works to create these resilient systems by restoring habitat throughout the Twin Cities.

We're all in this together

None of our work will completely solve the issues created by climate change, but the more progress we can make in concert with other landowners and partner agencies, the better we'll be able to combat climate change and work toward climate justice.

We're lucky to partner with other great organizations like Mississippi Park Connection in an effort to diversify our urban tree canopy. And we're honored to work with Wakaŋ Tipi Awaŋyaŋkapi (formerly Lower Phalen Creek Project) to incorporate culturally significant plant species and Indigenous ways of knowing into restorations like the one at Waḳaƞ Ṭípi, the future home of the Wakáŋ Tipi Center.

If you want to get involved with our land conservation efforts, sign up to volunteer at one of more than 35 active FMR restoration sites throughout the metro, or reach out about land protection opportunities in your area.