Climate change, climate justice and FMR's Land Use & Planning program

Impacts of climate change can be seen both in the erosion pictured here at Pine Bend Bluffs (left) fueled by intense rain events, and in the flooding at Harriet Island (right). Climate change makes park access and riverfront development planning even more important. (Left and center photos by Tom Reiter)

Climate change is already bringing dramatic shifts to Minnesota: Hotter average temperatures across the state, including warmer winters; more frequent, more intense rain and storm events leading to more flash flooding; more frequent late-summer droughts; and shifting ecosystems. The burden of these impacts falls disproportionately and unjustly on people with lower incomes and Black, Indigenous, and People of Color.

At FMR, each of our programs intersects with climate change and climate justice. The Land Use & Planning program works within metro river communities to ensure that public access, scenic views, historic preservation and environmental quality are respected. Here are just a few ways we're thinking about climate change and justice in that work.

Advocating for parks in every neighborhood

Parks are important as both a treatment and a cure for climate change. As wildlife habitat is degraded and put under increasing pressure from climate change, parks protect special places and can manage them for climate resilience. A continuous corridor of quality habitat along the Mississippi River creates a safe route for migrating wildlife, including those that might be moving to new areas as their traditional homes become unlivable.

Parks are also important refuges for people facing the stresses of climate change. Being outdoors in parks boosts mental and physical health. Green spaces and shade trees away from pavement and near water can provide cooler places to go on Minnesota's increasingly hot days. For lower-income residents who don't have air conditioning or can't afford to run it, being outdoors may be safer than staying indoors on a hot day.

Park access is disproportionate

Unfortunately, in Minnesota as well as across the nation, our park systems are inequitable. The Trust for Public Land's 2021 ParkScore rankings found that both Minneapolis and St. Paul have failed to provide equal open space across their entire cities. Neighborhoods with more low-income residents and/or residents of color have much less park space.

As the Pioneer Press noted in an article about the rankings: "In St. Paul, there's 30 percent less park space for residents of neighborhoods where most people identify as people of color, and 35 percent less for residents of low-income neighborhoods.

"In Minneapolis, there's 58 percent less space for residents of neighborhoods where most people identify as people of color and 65 percent less for low-income areas." (These figures are in comparison to majority-white neighborhoods and neighborhoods with the highest incomes.)

This is an injustice. It leaves certain neighborhoods out of the climate resilience and health benefits that parks provide. A recent study in the journal Nature found that Black and Hispanic residents are exposed to more intense urban heat island effects than white residents, due to living in neighborhoods with more pavement and less grass and trees. People living below the poverty line are 50% more exposed to heat island effects than their wealthier neighbors.

The study also found a correlation between urban heat islands and neighborhoods that were redlined; more proof that people, both historically and in the present day, haven't had equitable access to green space and the refuge it provides.

A different study found that Minneapolis neighborhoods that were historically redlined are an average of 11 degrees hotter than those that were not. Heat is a proven killer, especially for people with chronic medical conditions.

What we're doing to promote park access

We believe that the Mississippi River belongs to all of us and that everyone should benefit equitably from its resources. This includes parkland near the river.

We regularly advocate for expansive public parks throughout the Twin Cities' entire riverfront. This is especially true when riverfront redevelopment presents opportunities — or potential barriers — for increased public access, such as at the Island Station site in St. Paul or Mississippi Dunes in Cottage Grove.

We also know that having parks isn't enough; residents have to be able to get to them. That's why we also support a full view of what it means to have an accessible, equitable and affordable community. We expect big riverfront development projects to include affordable housing and multimodal transportation options so that everyone has the opportunity to connect with the river.

The former Island Station power plant property in St. Paul is being redeveloped for apartments. Thanks to FMR's advocacy, the site's river shoreline and unique backwater bay will become new public parkland.

Shaping development plans to respond to our shifting climate

Climate change poses a severe risk to many of the river's resources. Plants and animals are under pressure as habitats change and degrade. Land and water are at risk, too.

Our management of the Mississippi River here in the Twin Cities matters not just to locals but to all communities downstream that also turn to the river. Millions of people draw their drinking water from the Mississippi and swim and fish in the river.

The water quality issues that erosion and stormwater overflows create downstream are bound to disproportionately impact communities with fewer resources to treat their drinking water.

What we're doing to protect riverfront in development plans

We can expect Minnesota's future to include not only more excessively hot days, but also more extreme storms. When it comes to riverfront development and increasing rains, our planning standards around stormwater and erosion need to evolve, particularly in sensitive areas along the river.

Although erosion along the river is a natural process, our choices and actions around blufftop and shoreline development, stormwater management and climate change can exacerbate the issue and put life, property and the integrity of the river at greater risk.

FMR has worked for many years to bring new Mississippi River Corridor Critical Area development standards to fruition. Cities are in the process of adopting updated ordinances with stronger and more consistent rules about shoreline and bluff setbacks, stormwater treatment, vegetation management and other river protections.

But a booming real estate market is already testing the strengths of these standards and the resolve of local elected officials to stand behind them. We're seeing bluff setback requirements being challenged in cities from Minneapolis to Mendota Heights.

We expect to increasingly weigh in on metro development proposals — especially those seeking variances from the new river rules — with an eye to erosion control, landslide prevention and stormwater management.

Buildings built on bluffs, like this one in Lilydale, accelerate erosion issues that place structures, water quality, and lives at risk.

What we're doing to protect wildlife habitat in development plans

The new Mississippi River Corridor Critical Area ordinances can help protect wildlife, too.

Climate change will drive many species to seek out new habitat as their traditional range becomes uninhabitable. For birds, this journey may follow the Mississippi River. The river is a crucial migratory corridor for about 40% of all North American migrating birds. Roughly 270 bird species live in or travel through the Twin Cities river flyway.

Already, bird populations are experiencing significant collapse and are under continued threat. One of those threats is human-built structures: In the U.S. it's estimated that 600 million birds are killed in window strikes each year.

We can help balance growing cities and habitat protection to reduce deaths in bird populations facing catastrophic declines. One way to do this is to require bird-friendly lighting design, building design and building materials (such as fritted glass) in all new development along the river. We can also strengthen vegetation management requirements to increase native plantings and wildlife habitat along the river.

The Twin Cities' riverfront communities will have the opportunity to add these requirements to their new MRCCA ordinances in the near future. Minneapolis is already doing so. Learn more about how to get involved in advocating for your community's MRCCA ordinance.

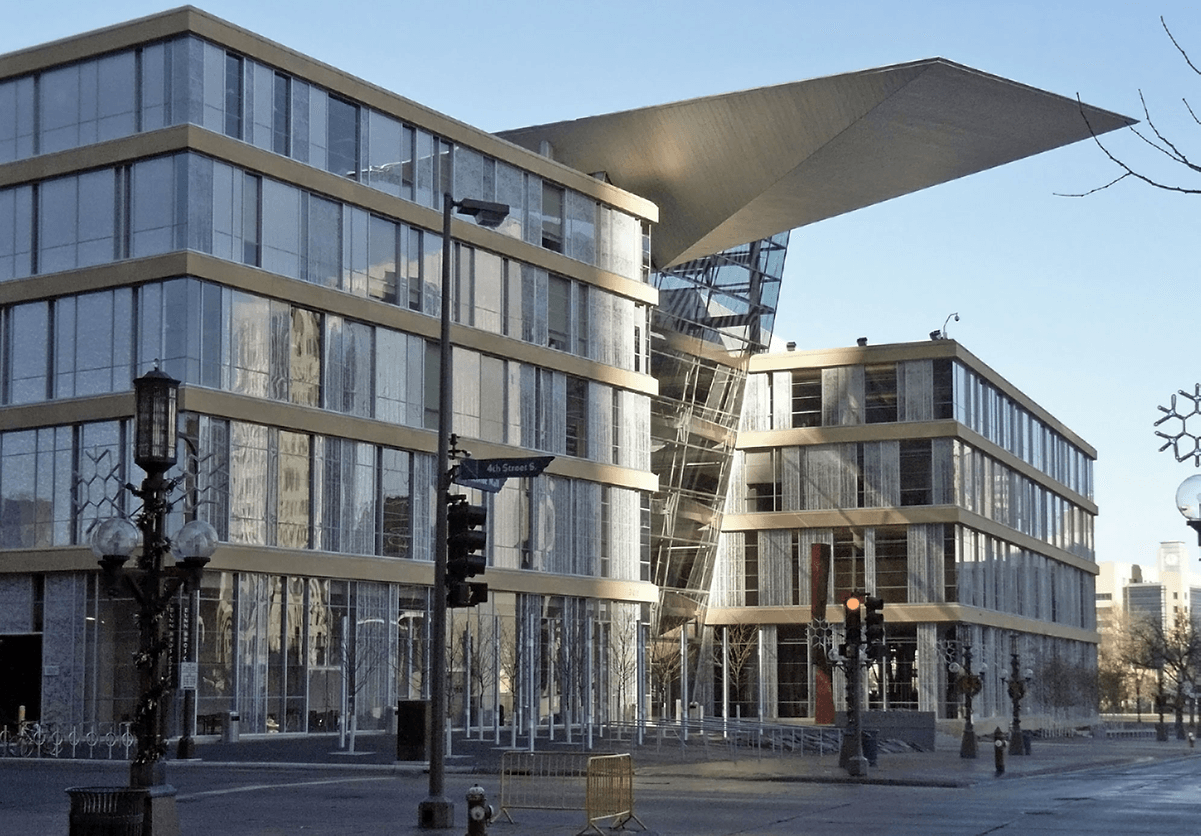

The Minneapolis Public Library's Central Library building is an example of bird-safe design. To reduce reflections that mimic habitat or sky and confuse birds, glass surfaces are angled and patterned. Trees planted very close to the building provide additional screening. (Photo: Payton Chung)

Join us

Sign up as a River Guardian, and we'll email you when there's a chance to act quickly to address issues like these at the intersection of climate change, our river corridor and environmental justice.